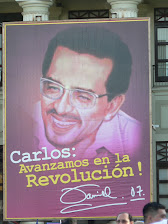

Aldo Díaz Lacayo’s article – Without a party the revolution is difficult – appeared in Managua’s El Nuevo Diario last November. It is a vital contribution to understanding the controversial role of the newly established Citizens’ Power Councils and their relationship to both the FSLN (Sandinista National Liberation Front) and the Ortega government.

Díaz is a prominent Nicaraguan diplomat and historian. A leading FSLN ideologue, he is a close collaborator of Daniel Ortega. He was named ambassador to the UN but has been unable to assume duties in New York for health reasons.

His article helps to debunk the notion of the monolithic character of the FSLN. The Sandinista party is a mass movement and is home to many diverse currents and conflicting interest groups, including (as Díaz points out) an organized group of capitalist investors.

Below is my English translation of the article. The original Spanish appears following the end notes.

Felipe Stuart C.

Managua

Without a party the revolution is difficult

By Aldo Díaz Lacayo

El Nuevo Diario | noviembre 23, 2007

http://www.elnuevodiario.com.ni/opinion/2567

The Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional [Sandinista National Liberation Front/FSLN] is more a circumstantial party [partido presentido ](i) than an organic entity. Leaders at all levels feel part and even active members of its structure, but they are not. And the few who really are active are aware of its organic weakness.

This is not a new situation. It is a consequence of the brutal demobilization of 1990; a product of the “save your own skin” syndrome that attacked the whole world left after the fall of real socialism; of the 1994 modernicist (ii) rupture that offered itself as a supposed surpassing of that syndrome, convinced that the historic Frente Sandinista would never again return to power; of the withdrawal of the counterpart (iii) for electoral reasons; and then two intervening electoral defeats that reduced to a minimum any expectation of getting back into government.

In other words, the Frente Sandinista’s return to government took place at a time when the party’s institutions were extremely weak, and in a situation of maximum ideological heterogeneity. It occurred in a country bankrupted by neoliberalism aggravated by the oil crisis; in a situation of great world instability and hence a revolutionary international ambience. Its return to government took place in highly contradictory conditions: very negative within the country but extraordinarily positive externally, even taking into account Nicaragua’s weakness in the face of imperialism.

The fundamental challenge of Daniel Ortega Saavedra’s government is how to surmount this new national and international reality given such structural weakness. He cannot evade that challenge. As well, he is obliged to meet it by giving preference to strategic solutions stemming from his revolutionary commitment. That means he must cope with headwinds and risk inevitable errors and the outburst of old and new contradictions. He has to do that to combat the dictatorship of global capitalism (as he calls it), now in crisis, and to consolidate the revolutionary tendency on the national level, and throughout the Americas and the South as a whole.

That is the structural background to the discussion that is taking place within Sandinismo (iv) and in our country. This background is real, but not yet grasped. Precisely for that reason, the discussion arising within the circumstantial party [FSLN] is projected to public opinion as personal differences, rather than the expression of objective contradictions. It is cast as a discussion between organic-historic party leaders and de facto upstarts, ignoring that the scaling of the struggle always produces new leaderships; and, in that sense, all authorities are in practice de facto.

It’s true that personality differences impinge on the handling of political-ideological contradictions. Holding positions of power strengthens one’s capacity to handle them, as in the case of the current discussion. One aggravating factor is that one of those positions is represented by the wife of the president. That lends an undesirable family bias to the discussion. However, despite all its potential graveness, none of that annuls the existence of the objective conditions.

The fundamental contradiction is that the thesis of a social democratic socialism is being promoted within the circumstantial party though the commercial activism of well known leaders – and also with the undesirable, but natural support of the local right, and their counterparts in all latitudes – while President Daniel Ortega Saavedra has decided to orient his government to revolutionary socialist positions along the same lines as the Sandinista revolution and what is occurring in South America.

That is Daniel Ortega’s explicit political will, whether or not he is managing to impart his government with a revolutionary socialist orientation. He is doing that alone, with the active support of his wife Rosario [Murillo] He is aware that this adds an important subjective element to the fundamental contradiction, no doubt in order to get to its root and overcome it. He is applying that line without concession either to the circumstantial party or the opposition. He is confronting in a combative spirit limitations imposed on him by general conditions in which he is operating, and he is taking on the contradictions that this confrontation is producing, above all that between his heartfelt discourse and the reality.

That is Daniel Ortega’s explicit political will, whether or not he is managing to impart his government with a revolutionary socialist orientation. He is doing that alone, with the active support of his wife Rosario [Murillo] He is aware that this adds an important subjective element to the fundamental contradiction, no doubt in order to get to its root and overcome it. He is applying that line without concession either to the circumstantial party or the opposition. He is confronting in a combative spirit limitations imposed on him by general conditions in which he is operating, and he is taking on the contradictions that this confrontation is producing, above all that between his heartfelt discourse and the reality. The situation becomes complicated because prior to the consolidation of the South American revolutionary tendency, the social democratic orientation was general throughout the South and then came to dominate the ranks of the Frente Sandinista, also in a circumstantial way. And, as well, because the contradiction between social democratic socialism and revolutionary socialism is still not fully developed. It is not even foreseeable at this time in definitive form. Only the government, and more concretely President Daniel Ortega, has the capacity and hence the responsibility to cut through this impasse.

The contradiction has suddenly taken form in the Citizens’ Power Councils (CPC) that the government has designed as its basic instrument to handle, and if possible, overcome the national crisis through a socialist orientation and through mobilizing the citizenry. Their very nature, therefore, imbues the CPCs with a highly political-ideological potential and makes them the likely structure of a real new party, drawing in citizens of other political sympathies and thereby reactivating the Sandinista revolution. Frequent social mobilization inevitably results in increased ideological consciousness of the people.

The contradiction has suddenly taken form in the Citizens’ Power Councils (CPC) that the government has designed as its basic instrument to handle, and if possible, overcome the national crisis through a socialist orientation and through mobilizing the citizenry. Their very nature, therefore, imbues the CPCs with a highly political-ideological potential and makes them the likely structure of a real new party, drawing in citizens of other political sympathies and thereby reactivating the Sandinista revolution. Frequent social mobilization inevitably results in increased ideological consciousness of the people. Given the actual condition of the Frente Sandinista and the country, the CPCs were born from power and logically for power. For that reason they are in contradiction with the established partisan and national powers. That same reason explains why they exacerbate contradictions within the circumstantial party and provoke radical rejection by the right of all stripes. All of this is aggravated because they are starting up with activists with ideological deficiencies and with little or no awareness of the contradiction involved, motivated to act by policies of leaders who are also in power, and thereby taking up their defense.

The ideological corollary of this critical analysis to the new Sandinista reality in its national context, without qualifying it in any way, is that the circumstantial party is a permanent cause of political-ideological contradictions. Political struggles for control of the party dilute its ideological goals and run the risk of keeping it in permanent instability, forever on the edge of splits, or being converted into a traditional party of a democratic-representative ilk, without grassroots support. To put it another way, the revolution becomes much more difficult without a real, ideologically united party.

Translator’s Endnotes

(i) The original Spanish reads: “Más que orgánico, el Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional es un partido presentido.” The author explains his use of this term (presentido) in the very next sentence. He uses it several times later in the article without attempting to qualify his meaning, leaving it open to various perceptions.

(ii) The author, in a letter to the editor of El Nuevo Diario, protested that the copy editor had changed his word “modernicista” to “modernista.” While acknowledging he had used a neologism that does not appear in standard Spanish dictionaries, he explained that the word has come into use with a special twist in meaning that was vital to his point. “As I understand it, he wrote, “in political-ideological terms modernicismo implies a rationalization of modernity. That is, using the concept of modernity in logical but intangible terms in order to justify a decision. In the political-ideological case I refer to, I mean the justification for abandoning the historical orientation of the Frente Sandinista.” See Con todo respeto, corrigiendo al corrector - http://www.elnuevodiario.com.ni/opinion/2722

(iii) A reference to a social democratic split from the FSLN that subsequently formed the Sandinista Renovation Movement (MRS), an electoral party.

(iv) The term Sandinismo refers to the broad Sandinista movement and culture of Nicaraguans and takes in a majority of people with anti-imperialist traditions and concepts.

<<<<<<<<<<< >>>>>>>>>>>>

Sin partido la revolución es difícil

Por Aldo Díaz Lacayo

15:45 - 23/11/2007

http://www.elnuevodiario.com.ni/opinion/2567

Más que orgánico, el Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional es un partido presentido. Dirigentes de todos los niveles se sienten parte y hasta miembros activos de su estructura, pero no lo son. Y los pocos que realmente lo son, están conscientes de su debilidad orgánica.

Esta situación no es nueva, es consecuencia de la brutal desmovilización de 1990, producto del síndrome del “sálvese quien pueda” que atacó a la izquierda universal, después de la caída del socialismo real; de la ruptura modernista de 1994, que se dio como supuesta superación de este síndrome con la convicción de que el Frente Sandinista histórico jamás regresaría al gobierno; del repliegue de la contraparte por razones electorales; y desde luego de las dos derrotas electorales intermedias, que disminuyeron al máximo la expectativa de este regreso.

En otras palabras, el regreso al gobierno del Frente Sandinista se dio en condiciones partidarias de extrema debilidad institucional y de máxima heterogenización ideológica; en un país en bancarrota neoliberal, agravada por la crisis petrolera; en medio de una gran inestabilidad mundial, y por lo mismo en un entorno internacional revolucionario. Un regreso, pues, en condiciones políticas altamente contradictorias: muy negativas a lo interno, pero extraordinariamente positivas a lo externo, aún considerando la debilidad de Nicaragua frente al imperialismo.

Cómo acometer esta nueva realidad, nacional e internacional, con tanta debilidad estructural es el reto fundamental del gobierno de Daniel Ortega Saavedra. No puede soslayarlo. Y está obligado, además, a asumirlo privilegiando soluciones estratégicas desde su compromiso revolucionario; contra el tiempo, a riesgo de inevitables errores y del afloramiento de viejas y nuevas contradicciones. Para combatir la dictadura del capitalismo global, como él la llama, actualmente en crisis, y consolidar la tendencia revolucionaria, nacional, americana y del Sur.

Éste es el trasfondo estructural de la discusión que se está dando en el sandinismo, y en el país nacional. Un trasfondo real pero aún no asumido. Precisamente por esto la discusión aparece a lo interno del partido presentido y se proyecta a la opinión pública como diferencias personales, y no como expresión de contradicciones objetivas; como una discusión entre autoridades partidarias orgánico-históricas y de hecho-advenedizas; ignorando que en la práctica todas las autoridades son de hecho, y que el escalamiento de la lucha siempre produce nuevos liderazgos.

Es cierto que las diferencias de personalidades inciden en el manejo de las contradicciones político-ideológicas, y que las posiciones de poder potencian este manejo, como es el caso de la discusión actual; con el agravante de que una de estas posiciones está representada por la esposa del Presidente, lo cual le imprime a la discusión un sesgo familiar no deseado. Sin embargo, a pesar de toda su gravedad potencial, nada de esto anula la existencia de contradicciones objetivas.

La contradicción fundamental es que a lo interno del partido presentido y con el activismo mercantilista de connotados dirigentes --y también con el indeseable, pero natural respaldo de la derecha local y de todas las latitudes--, se impulsa la tesis de un socialismo socialdemócrata; mientras que el presidente Daniel Ortega Saavedra ha decidido orientar su gobierno hacia posiciones socialistas revolucionarias, en la misma línea de la revolución sandinista y de la que se está dando en Suramérica.

Con independencia de que el Presidente esté logrando darle a su gobierno una orientación socialista revolucionaria, ésta es su voluntad política explícita. Y la está implementando sólo con el apoyo activo de su esposa Rosario, consciente de que le agrega un importante elemento subjetivo a la contradicción fundamental, sin duda para radicalizarla y superarla; aplicándola sin concesiones, ni al partido presentido ni a la oposición; enfrentando con espíritu combativo las limitaciones que le imponen las condiciones generales en que está actuando, y asumiendo las contradicciones que este enfrentamiento produce, en primer lugar entre su discurso sentido y la realidad.

La situación se complica porque antes de la consolidación de la tendencia revolucionaria sudamericana, y en general del Sur, y también en forma presentida, la orientación socialdemócrata primaba en las filas del Frente Sandinista; y también porque aún no está plenamente conformada la contradicción socialismo socialdemócrata/socialismo revolucionario. Ni siquiera es previsible en este momento su conformación definitiva. Sólo el gobierno, y más concretamente el presidente Daniel Ortega Saavedra, tiene la capacidad y desde luego la responsabilidad de romper este impasse.

De pronto, la contradicción ha tomado cuerpo en los Consejos de Poder Ciudadano, CPC, diseñados como instrumento fundamental del gobierno para manejar, y de ser posible, revertir la crisis nacional con orientación revolucionaria, a través de la movilización ciudadana. Por su propia naturaleza, entonces, son una instancia de altísimo potencial político-ideológico y probable estructura del nuevo partido real, cooptando a ciudadanos de otras simpatías políticas y reactivando así la revolución sandinista. Porque inevitablemente la frecuencia de la movilización social se traduce en aumento de la conciencia ideológica del pueblo.

Por otra parte, por las actuales condiciones del Frente Sandinista y del país, los CPC han nacido desde el poder, lógicamente para el poder, y por la misma razón en contradicción con el poder establecido, partidario y nacional, lo cual explica porqué exacerban las contradicciones a lo interno del partido presentido y provocan el rechazo radical de la derecha, en todos sus matices. Y todo esto con el agravante de que están arrancando con una militancia con deficiencias ideológicas, con poca o ninguna conciencia de la contradicción planteada, actuando en consecuencia por motivaciones políticas alrededor de liderazgos también de poder, y asumiendo así su defensa.

El corolario ideológico de este análisis crítico, sin valoraciones de ninguna especie, sobre la nueva realidad sandinista en el contexto nacional, es que el partido presentido es causa permanente de contradicciones político-ideológicas. Porque los objetivos ideológicos se diluyen en las luchas políticas por el control del partido, con el riesgo de mantenerlo en permanente inestabilidad, siempre al borde de la ruptura, o de convertirlo en un partido tradicional, sin arraigo popular, al mejor estilo democrático-representativo. Dicho de otro modo, sin partido real, ideológicamente unitario, la revolución se hace mucho más difícil.