Intoduction

My comments on this theme and article appear at the end of compañero Riddell's very much needed article "From Marx to Morales: Indigenous Socialism and the Latin Americanization of Marxism." They follow the Endnotes for the main article.

Riddell's article first appeared in

Socialist Voice at http://www.socialistvoice.ca/?p=299

Felipe Stuart C.

Managua

By John Riddell  John Riddell is co-editor of Socialist Voice and editor of The Communist International in Lenin's Time, a six-volume anthology of documents, speeches, manifestos and commentary. This article is based on his talk at the Historical Materialism conference at York University in Toronto on April 26, 2008.

John Riddell is co-editor of Socialist Voice and editor of The Communist International in Lenin's Time, a six-volume anthology of documents, speeches, manifestos and commentary. This article is based on his talk at the Historical Materialism conference at York University in Toronto on April 26, 2008. Over the past decade, a new rise of mass struggles in Latin America has sparked an encounter between revolutionists of that region and many of those based in the imperialist countries. In many of these struggles, as in Bolivia under the presidency of Evo Morales, Indigenous peoples are in the lead.

Latin American revolutionists are enriching Marxism in the field of theory as well as of action. This article offers some introductory comments indicating ways in which their ideas are linking up with and drawing attention to important but little-known aspects of Marxist thought.

Eurocentrism A good starting point is provided by the comment often heard from Latin American revolutionists that much of Marxist theory is marked by a "Eurocentric" bias. They understand Eurocentrism as the belief that Latin American nations must replicate the evolution of Western European societies, through to the highest possible level of capitalist development, before a socialist revolution is possible. Eurocentrism is also understood to imply a stress on the primacy of industrialization for social progress and on the need to raise physical production in a fashion that appears to exclude peasant and Indigenous realities and to point toward the dissolution of Indigenous culture.[1]

Marx's celebrated statement that "no social order ever perishes before all the productive forces for which there is room in it have developed"[2] is sometimes cited as evidence of a Eurocentric bias in Marxism. Karl Kautsky and Georgi Plekhanov, Marxist theorists of the pre-1914 period, are viewed as classic exponents of this view. Latin American writer Gustavo Pérez Hinojosa quotes Kautsky's view that "workers can rule only where the capitalist system has achieved a high level of development"[3] — that is, not yet in Latin America.

The pioneer Marxists in Latin American before 1917 shared that perspective. But after the Russian Revolution a new current emerged, now often called "Latin American Marxism." Argentine theorist Néstor Kohan identifies the pioneer Peruvian Communist José Carlos Mariátegui as its founder. Mariátegui, Kohen says, "opposed Eurocentric schemas and populist efforts to rally workers behind different factions of the bourgeoisie" and "set about recapturing `Inca communism' as a precursor of socialist struggles."[4]

National subjugation

Pérez Hinojosa and Kohen both take for granted that Latin American struggles today, as in Mariátegui's time, combine both anti-imperialist and socialist components. This viewpoint links back to the analysis advanced by the Communist International in Lenin's time of a world divided between imperialist nations and subjugated peoples.[5] Is this framework still relevant at a time when most poor countries have formal independence? The central role of anti-imperialism in recent Latin American struggles would seem to confirm the early Communist International's analysis.

Pérez Hinojosa tells us that Mariátegui recognized the impossibility of national capitalist development in semi-colonial countries like Peru. The revolution would be "socialist from its beginnings but would go through two stages" in realizing the tasks first of bourgeois democratic and then of socialist revolution. Moreover, the Peruvian theorist held that "this socialist revolution would be marked by a junction with the historic basis of socialization: the Indigenous communities, the survivals of primitive agrarian communism."[6]

Subsequently, says Kohen, the "brilliant team of the 1920s," which included Julio Antonio Mella in Cuba, Farabundo Martí in El Salvador, and Augusto César Sandino in Nicaragua, "was replaced … by the echo of Stalin's mediocre schemas in the USSR," which marked a return to a mechanical "Eurocentrist" outlook.[7]

Writing from the vantage point of Bolivia's tradition of Indigenous insurgency, Alvaro García Linera attributes Eurocentric views in his country to Marxism as a whole, as expressed by both Stalinist and Trotskyist currents. He states that Marxism's "ideology of industrial modernisation" and "consolidation of the national state" implied the "`inferiority' of the country's predominantly peasant societies."[8]

Cuban revolution

Cuban revolution In Kohen's view, the grip of "bureaucratism and dogmatism" was broken "with the rise of the Cuban revolution and the leadership of Castro and Guevara."[9] Guevara's views are often linked to those of Mariátegui with regard to the nature of Latin American revolution — in Guevara's words, either "a socialist revolution or a caricature of a revolution."[10] That claim was based on convictions regarding the primacy of consciousness and leadership in revolutionary transitions that were also held by Mariátegui.

Guevara also applied this view to his analysis of the Cuban state and of Stalinized Soviet reality. Guevara inveighed against the claim of Soviet leaders of his time that rising material production would bring socialism, despite the political exclusion, suffering, and oppression imposed on the working population.[11] (See "Che Guevara's Final Verdict on Soviet Economy," in Socialist Voice, June 9, 2008.)

Marx's views In Kohen's opinion, the Cuban revolution's leading role continued in the 1970s, when it "revived the revolutionary Marxism of the 1920s (simultaneously anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist) as well as Marx's more unfamiliar works—above all his later works that study colonialism and peripheral and dependent societies. In these writings Marx overcomes the Eurocentric views of his youth."[12]

Kohen identifies the insights of the "Late Marx" as follows:

History does not follow an unvarying evolutionary path.

Western Europe does not constitute a single evolutionary centre through which stages of historical development are radiated outwards to the rest of the world.

"Subjugated peoples do not experience `progress' so long as they remain under the boot of imperialism."[13]

Latin American thought here rests on the mature Marx's views on capitalism's impact on colonial societies, such as Ireland. It also intersects with Marx's late writings and research known to us primarily through Teodor Shanin's Late Marx and the Russian Road.[14] Shanin's book can now be usefully reread as a commentary on today's Latin American struggles.

Marx devoted much of his last decade to study of Russia and of Indigenous societies in North America. His limited writings on these questions focused on the Russian peasant commune, the mir, which then constituted the social foundation of agriculture in that country.

Russia's peasant communes The Russian Marxist circle led by Plekhanov, ancestor of the Bolshevik party, believed that the mir was doomed to disappear as Russia was transformed by capitalist development. We now know that Marx did not agree. In a letter to Vera Zasulich, written in 1881 but not published until 1924, he wrote that "the commune is the fulcrum for social regeneration in Russia." The "historical inevitability" of the evolutionary course mapped out in Capital, he stated, is "expressly restricted to the countries of Western Europe."[15]

The preliminary drafts of Marx's letter, included in Shanin's book, display essential agreement with the view of the revolutionary populist current in Russia, the "People's Will," that the commune could coexist harmoniously with a developing socialist economy.[16]

Ethnological Notebooks These drafts drew on Marx's extensive studies of Indigenous societies during that period, a record of which is available in his little-known Ethnological Notebooks.[17] We find his conclusions summarized in a draft of his letter to Zasulich: "The vitality of primitive communities was incomparably greater than that of Semitic, Greek, Roman, etc. societies, and, a fortiori, that of modern capitalist societies."[18]

In her study of these notebooks, Christine Ward Gaily states that where such archaic forms persist, Marx depicts them fundamentally "as evidence of resistance to the penetration of state-associated institutions," which he views as intrinsically oppressive.[19] The clear implication is that such archaic survivals should be defended and developed.

The Marxists of Lenin's time were not aware of this evolution in Marx's thinking. Thus Antonio Gramsci could write, a few weeks after the Russian October uprising, "This is the revolution against Karl Marx's Capital. In Russia, Marx's Capital was more the book of the bourgeoisie than of the proletariat."[20] Yet despite their limited knowledge of Marx's views, the revolutionary generation of Lenin, Luxemburg, Trotsky, Bukharin, Gramsci, and Lukács reasserted Marx's revolutionary stance in combat with the "Eurocentrist" view associated with Karl Kautsky and the pre-war Socialist International that socialist revolution must await capitalism's fullest maturity and collapse.

Shanin generalizes from Marx's approach to Russia in 1881 in a way that links to a second characteristic of Latin American revolution. "The purest forms of `scientific socialism' … invariably proved politically impotent," he argues. "It has been the integration of Marxism with the indigenous [i.e. home-grown] political traditions which has underlain all known cases of internally generated and politically effective revolutionary transformation of society by socialists."[21]

Here we have a second field of correlation with the Latin American revolutionary experience, with its strong emphasis on associating the movement for socialism with the tradition of anti-colonial struggle associated with the figures of the great aboriginal leaders and of Bolívar, Martí, and Sandino. This fusion of traditions emerges as a unique strength of Latin American Marxism.

Mariátegui captured this thought in a well-known passage:

"We certainly do not wish socialism in America to be a copy and imitation. It must be a heroic creation. We must give life to an Indo-American socialism reflecting our own reality and in our own language."[22]

Following the October revolution of 1917, Marx's vision of the mir's potential was realized in practice. The mir had been in decline for decades, and by 1917 half the peasants' land was privately owned. But in the great agrarian reform of 1917-18, the peasants revived the mir and adopted it as the basic unit of peasant agriculture. During the next decade, peasant communes co-existed constructively with the beginnings of a socialist economy. By 1927, before the onset of Stalinist forced collectivization, 95% of peasant land was already communally owned.[23]

There is a double parallel here with present Latin American experience. First, the Bolsheviks' alliance with the peasantry is relevant in Latin American countries where the working class, in the strict sense of those who sell their labour power to employers, is often a minority in broad coalitions of exploited producers. Second, survivals of primitive communism, including communal landholding, are a significant factor in Indigenous struggles across this region.

National emancipation A third correspondence can be found in the Bolsheviks' practice toward minority peoples of the East victimized and dispossessed by Tsarist Russian settler colonialism. Too often, discussions of the Bolsheviks' policy on the national question stop short with Stalin and Lenin's writings of 1913-1916, ignoring the evolution of Bolshevik policy during and after the 1917 revolution. Specifically:

The later Bolsheviks did not limit themselves to the criteria of nationhood set out by Stalin in 1913.[24] They advocated and implemented self-determination for oppressed peoples who were not, at the time of the 1917 revolution, crystallized nations or nationalities.

They went beyond the concept that self-determination could be expressed only through separation. Instead, they accepted the realization of self-determination through various forms of federation.

They implemented self-determination in a fashion that was not always territorial.

Their attitude toward the national cultures of minority peoples was not neutral. Instead, they committed substantial political and state resources to planning and encouraging the development of these cultures.[25]

On all these points, the Bolshevik experience closely matches the revolutionary policies toward Indigenous peoples now being implemented in Bolivia and other Latin American countries.

Ecology and materialism Finally, a word on ecology. The boldest governmental statements on the world's ecological crisis are coming from Cuba, Bolivia, and other anti-imperialist governments in Latin America.[26] The influence of Indigenous struggles is felt here. Bolivian President Evo Morales points to the leading role of Indigenous peoples, "called upon by history to convert ourselves into the vanguard of the struggle to defend nature and life."[27]

This claim rests on an approach by many Indigenous movements to ecology that is inherently revolutionary. Most First-World ecological discussion focuses on technical and market devices, such as carbon trading, taxation, and offsets, that aim to preserve as much as possible of a capitalist economic system that is inherently destructive to the natural world. Indigenous movements, by contrast, begin with the demand for a new relationship of humankind to our natural environment, sometimes expressed in the slogan, "Liberate Mother Earth."[28]

These movements often express their demand using an unfamiliar terminology of ancestral spiritual wisdom — but behind those words lies a worldview that can be viewed as a form of materialism.

In pre-conquest Andean society, says Peruvian Indigenous leader Rosalía Paiva, "Each was a part of all, and all were of the soil. The soil could never belong to us because we are its sons and daughters, and we belong to the soil."[29]

Bolivian Indigenous writer Marcelo Saavedra Vargas holds that "It is capitalist society that rejects materialism. It makes war on the material world and destroys it. We, on the other hand, embrace the material world, consider ourselves part of it, and care for it."[30]

This approach is reminiscent of Marx's thinking, as presented by John Bellamy Foster in Marx's Ecology. It is entirely appropriate to interpret "Liberate Mother Earth" as equivalent to "close the metabolic rift."[31]

Hugo Chávez says that in Venezuela, 21st Century Socialism will be based not only on Marxism but also on Bolivarianism, Indigenous socialism, and Christian revolutionary traditions.[32] Latin American Marxism's capacity to link up in this way with what Shanin calls vernacular revolutionary traditions is a sign of its vitality and promise.

I will conclude with a story told by the Peruvian Marxist and Indigenous leader Hugo Blanco. A member of his community, he tells us, conducted some Swedish tourists to a Quechua village near Cuzco. Impressed by the collectivist spirit of the Indigenous community, one of the tourists commented, "This is like communism."

"No," responded their guide, "Communism is like this."[33]

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Related Reading

Hugo Blanco. The Fight for Indigenous Rights in the Andes Today [pdf]

John Riddell. COMINTERN: Revolutionary Internationalism in Lenin's Time [pdf]

John Riddell. The Russian Revolution and National Freedom

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Footnotes

[1] "Alvaro García Linera, "Indianismo and Marxism" (translated by Richard Fidler), in Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal.

David Bedford, "Marxism and the Aboriginal Question: The Tragedy of Progress," in Canadian Journal of Native Studies, vol. 14, no. 1 (1994), 102-103.

Hugo Blanco Galdos, letter to the author, December 17, 2007.

[2] Karl Marx, A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, in Karl Marx, Frederick Engels, Selected Works, Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1969, vol. 1, p. 504.

[3] Gustavo Pérez Hinojosa, "La heterodoxia marxista de Mariátegui." Rebelión, October 30, 2007..

[4] Néstor Kohan, "El marxismo latinoamericano y la crítica del eurocentrismo," in Con sangre en las venas, Mexico: Ocean Sur, 2007, pp. 10, 11.

[5] See, for example, V.I. Lenin's report on the National and Colonial Questions to the Communist International's second congress, in Collected Works, Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1969, vol. 31, pp. 240-41; and the subsequent congress discussion and resolution, in John Riddell, ed., Workers of the World and Oppressed Peoples, Unite!, New York: Pathfinder Press, 1991, vol. 1, pp. 216-290.

[6] Hinojosa, "Mariátegui."

[7] Kohen, "Eurocentrismo," p. 10.

[8] García Linera, "Indianismo."

[9] Kohen, "Eurocentrismo," p. 10.

[10] Ernesto Che Guevara, "Message to the Tricontinental," in Che Guevara Reader, Melbourne: Ocean Press, 2003, p. 354.

[11] See, for example, "Algunas reflexiones sobre la transición socialista," in Ernesto Che Guevara, Apuntes críticos a la Economía Política, Melbourne: Ocean Press, 2006, pp. 9-20.

[12] Kohan, "Eurocentrismo," pp. 10-11.

[13] Ibid., p. 11

[14] Teodor Shanin, ed., Late Marx and the Russian Road: Marx and the "Peripheries of Capitalism," New York: Monthly Review Press, 1983.

[15] Shanin, Late Marx, p. 124.

[16] Ibid., p. 12, 102-103.

[17] Lawrence Krader, ed., The Ethnological Notebooks of Karl Marx, Assen, NE: Van Gorcum, 1972.

[18] Karl Marx, Frederick Engels, Collected Works, Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1989, vol. 24, pp. 358-59.

[19] Christine Ward Gailey, "Community, State and Questions of Social Evolution in Marx's Ethnological Notebooks," in Anthropologica, vol. 45 (2003), pp. 47-48.

[20] Antonio Gramsci, "The Revolution against Das Kapital"

[21] Shanin, Late Marx, p. 255.

[22] Marc Becker, "Mariátegui, the Comintern, and the Indigenous Question in Latin America," in Science & Society, vol. 70 (2006), no. 4, p. 469, quoting from José Carlos Mariátegui, "Anniversario y Balance" (1928).

[23] Moshe Lewin, Russian Peasants and Soviet Power, New York: W.W. Norton, 1968, p. 85.

[24] J.V. Stalin, "Marxism and the National Question," in Works, Moscow: FLPH, 1954, vol. 2, p. 307.

[25] See Jeremy Smith, The Bolsheviks and the National Question, 1917-23, New York: St. Martin's Press, 1999;

John Riddell, "The Russian Revolution and National Freedom." Socialist Voice, November 1, 2006.

[26] See, for example, Evo Morales, Felipe Perez Roque, "Bolivia and Cuba Address the UN: Radical Action Needed Now to Stop Global Warming." Socialist Voice, September 26, 2007.

[27] Ibid.

[28] From a presentation by Vilma Amendra of the Association of Indigenous Councils of Northern Cauca (Colombia) at York University, Friday, January 11, 2008.

[29] Address to Bolivia Rising meeting in Toronto, April 5, 2008.

[30] Interview with Marcelo Saavedra Vargas, April 21, 2008.

[31] John Bellamy Foster, Marx's Ecology: Materialism and Nature, New York: Monthly Review Press, 2000.

[32] See, for example, speech by Chávez on December 15, 2006, summarized in "Chávez Calls for United Socialist Party of Venezuela." Socialist Voice, January 11, 2007.

[33] Blanco's remarks to an informal gathering in Toronto, September 16, 2008.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

FEEDBACK: Socialist Voice welcomes questions, comments and debate on the articles we publish. To comment on this article, go to www.socialistvoice.ca and use the "Feedback" box at the bottom of the page. (If the box isn't visible, click on the "Comments" link.)

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

COMMENT BY FELIPE STUART

John Riddell’s article “From Marx to Morales: Indigenous Socialism and the

Latin Americanization of Marxism” is a much needed contribution to today’s arsenal of Marxism for application in Abya Yala, or Indo-Black-Latino America, and logically for many other arena of global struggle against imperialist and capitalist depredation and exploitation. I hope it will be rapidly reproduced in other publications , and translated to Spanish by a native speaker of that language, and why not, into Quechua and other indigenous tongues.

In the course of my work in collaboration with Peruvian indigenous and campesino leader Hugo Blanco, a Marxist friend wrote, in the framework of an internet discussion list, a posting that expressed a concern that solidarity with indigenous struggles often passes over into idealist and ineffective nostalgia for a “return to nature,” for times past that cannot ever be again. He was concerned that we would end up denying "progressive" aspects of the history of imperialist expansion (such as the current revolutionary impact of the Black minority in the United States) by a misdirected effort to turn back the clock of history.

I responded with the following message, obviously edited to remove references to other individuals involved in a multi person exchange, and for space reasons.

Felipe Stuart C.

Managua

Neither Hugo Blanco nor I have argued for a nostalgic return to the good old days of an imagined primitive communism or even to the pre-Conquest days.

Hugo is very explicit on that question.

He says we do not want to return to the past. We want – he explains – to know and honor our past and take from it essential elements to struggle today for our future.

The essential elements he points to are the communistic traditions of social organization and the respect and love of nature – an integral cosmovision whose essential core can lay the basis for a new morality and cultural mode in the socialist transformation of our continent.

Mariátegui was one of the first Marxists in the western hemisphere to break from schematism, and to appreciate the contribution that indigenous traditions and culture could make to the anti-imperialist and anti- capitalist struggle in Indo-America, and to social transformation beyond capitalism.

I think Eurocentric Marxism and to some degree the Marxism taught by George Novack (a longtime leader of the U.S. Socialist Workers Party … lacks the benefit of Mariátegui’s contribution. We should recall that Mariátegui made this advance without the benefit of Marx’s ethnography notebooks and recent discussions of his nuanced and dialectical appreciation of the potential role of the Russian peasant commune. But he did have before him the revolutionary shift in Bolshevik policy on the nationalities question when they broke completely with pre-1917 schemas and embraced the national minorities, Islamic religious and cultural rights, autonomy for Soviet Jews, and so on.

Don’t get me wrong -- I deeply respect George Novack’s contribution and consider his writings to be indispensable tools in ongoing socialist educational work. Some of his writings on combined and uneven development are crucial to unraveling some of the tightest knots in understanding Indo-Afro-Latin American history, especially the false debate about feudal or capitalist social relations in colonial times. But a good dose of Mariátegui would have enabled George to avoid some pitfalls [a Google search for George Novack and/or Pathfinder Press will turn up quite a number of his books and essays].

The notion that the defeat of the ancient commune and the rise of class society were inevitable and progressive is one sided and ultimately false.

Ernest Mandel addresses that question in the Chapter on Labour, Necessary Product, Surplus Product of his major two-volume work Marxist Economic Theory. After describing the progressive functions of the “new possessing classes,” he makes the following observation:

“The technique of accumulation has been used to justify the appropriation of extensive material privileges. Even if it be historically indispensable, there is no reason to believe that it could not have been applied eventually by the collectivity itself” (p. 41, 1971 Merlin edition).

The shattering of the ancient commune and the forging of class society, exploitation and oppression, and the rise of the state were not inevitable.

Mandel also notes:

“The Marxist category of ‘historical necessity’ is moreover much more complex that popularisers commonly suppose. It includes, dialectically, both the accumulation of the social surplus which was carried out by the ancient ruling classes, and also the struggle of the peasants and slaves against these ruling classes, a struggle without which the fight for emancipation waged by the modern proletariat would have been infinitely more difficult” (p. 42, 1971 Merlin edition).

[We might now want to change his sentence to read: “the fight waged by the modern proletariat and subjugated semi-colonial and indigenous peoples would have been infinitely more difficult” (FSC)].

No serious modern thinker would express nostalgia for the conditions of existence of pre-class communal tribal life, or yearn for a return to such days. But, as Blanco argues, elements of that tradition survived and became central to indigenous cosmovision in Abya Yala (the Americas) and today are central to their resistance to imperialist and capitalist domination, and to their defense of nature against capitalist depredation.

Mandel makes an interesting point that relates to this discussion:

“It is only when the division of society into classes begins, when the social division of labour, and the need to justify exploitation appears, that ideology in the sense of ‘bad conscience’ can arise. The old mentality, based on primitive clan communism, slowly dissolves. But its vitality remains very great, and thousands of years have to pass before the last traces of these feelings of elementary solidarity disappear. It is, moreover, by utilizing these feelings of solidarity and co-operative discipline within a communistic society that the first ideologists in the service of the ruling classes endeavour to persuade the working classes to accept their situation of permanent inferiority. This is the ‘organic’ conception of society, which is worked out in order to justify a social division of labour identified with the division of society into rich and poor, privileged persons and producers, those who give orders and those who obey them.”

[At that point, Mandel offers an insightful footnote about Karl Polanyi’s fascination with naturalism. “A curious echo of this ‘organic conception of society is to be found in the writings of certain modern critics of economic liberalism, such as Karl Polanyi. The latter treats even slave owning society as a society which ‘integrated the individual into society’ and makes no distinction between the way a free member of a village community saw his position and the way this position appeared to a slave or a serf.”

We should also note that this line of thought is directly related to the historical role of religion. The rise of Christianity is propelled both by a social movement against slavery and oppression, and in a dialectical progression, the imposition of the naturalist ideology discussed by Mandel. But it remains to this day, also the “sigh of the oppressed”. Ditto for the Muslim faith, and many others.

The spiritualism of indigenous peoples is different. It is not ideological. It did not arise to justify or to camouflage exploitative and alienating social relations. Mandel also explains this difference very succinctly and well by in the opening paragraphs of Chapter 18, The Origin, Rise and Withering Away of Political Economy (Op cit., p. 690).

In today’s world of imperialist subjugation and capitalist destruction of the very material conditions of life (the environment), indigenous spiritualist cosmovision takes on a revolutionary potential when integrated into the international proletarian and plebian struggle for socialism.

I was puzzled by your court summary of how the Aztec empire was supposedly destroyed by a couple of hundred Spanish soldiers. Similar arguments are made about the defeat of the Inca, although it took the Conquistadores a bit longer and cost them much more to occupy the Andes. However, the military relationship of forces is only part of the explanation of the historical catastrophe of the European conquest, as seen from the point of view of the original inhabitants of Abya Yala. The main factor was not force of arms, but disease.

…………..

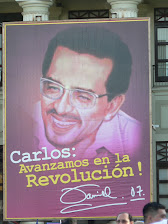

We do not weep or even sigh about the conquest, although sighs can be healthy and positive, and even weeping at times. But we do rejoice at the great and powerful resistance struggles. We do celebrate 500 years of Indigenous, Black, and Grassroots Resistance (I was one of the central organizers of the huge conference on that theme held in Managua the week of October 12, 1992 attended (it now seems ironic) by a young indigenous militant from Bolivia by the name of Evo Morales, and by Rigoberta Menchu who had just received the Nobel Peace award).

So I would like to turn your apparently ambiguous attitude towards indigenous tradition into an active pursuit of a great tradition, a cultural “rescate” (recovery).

I am reminded of the assertive words on the license plate in Quebec -- Je me souviens (I remember); or Longfellow’s poem Evangeline, A Tale of Acadie. It has been put to song in dozens of interpretations and formed the basis of novels and stories (see http://www.cyberacadien.com/?p=40).

Is it reactionary for the Quebecois or the Acadien to yearn for the times before the British conquest?

When we do that are we yearning to go back to feudalism, indentured labor, and survival farming in a climate and geography we poorly understood? I don’t think that is what characterizes these cultural expressions, any more than Hugo Blanco’s arguments are part of a movement to go back to a “Native” world of times past. They are assertions of pride in and for the oppressed and suppressed culture, for the language and song of the oppressed, for our traditions, for our elders and ancestors, for the blood of our resistance to conquerors and imperialists then and now. For our liberation! …………. (fin)

_DCE.jpg)

_DCE.jpg)

_DCE.jpg)