Below I am reproducing Fidler’s introduction and notes, followed by a commentary on the relevance of the article for analyzing the revolutionary process in Nicaragua.

Felipe Stuart

Managua

Catastrophic Equilibrium and Point of Bifurcation

by Álvaro García Linera

Introduction

by Richard Fidler

The following article, based on a speech given in December 2007 but only recently transcribed and published, is an important statement by a leading member of Evo Morales' government on the political situation in Bolivia in the wake of the Constituent Assembly's vote on a draft Political Constitution. The draft Constitution is to be put to a popular vote for adoption later this year.

Álvaro García Linera, Bolivia's Vice-President, is a former leader of the Tupac Katarí guerrilla army, subsequently employed as a university sociologist. He is also a prominent Latin American Marxist strongly influenced by post-World War II European non-Stalinist Marxist currents inspired by the ideas of the Italian communist leader and political theorist Antonio Gramsci.

Gramsci, who died in 1937, was an innovative Marxist thinker who wrote extensively on the concept of cultural hegemony and its role as an ideological mainstay of capitalist societies.

Some readers may be surprised by García Linera's frequent invocation of Gramscian "hegemony" in the Bolivian context, as that concept is often associated primarily with Marxist attempts to explain the particular problems of mass consciousness as they arise in the complex class societies of the imperialist countries. However, there is a long line of thinking among Latin American Marxists influenced by Gramsci; it goes back to José Carlos Mariátegui, the Peruvian communist, who lived in Italy for a period during the 1920s and was acquainted with Gramsci's writings. These Latin Americans, like Gramsci, also drew on the early Communist International's use of the concept of hegemony in analyzing the relationship between the minority proletariat and the non-proletarian (largely peasant) masses in the colonies and semicolonies. That theoretical legacy was explained more than three decades ago by Perry Anderson in a seminal article in New Left Review, "The Antinomies of Antonio Gramsci" (NLR 100, November-December 1976), which bears re-reading today. (See especially pp. 15-18.)

García Linera's title, in the original Spanish, is "Empate catastrófico y punto de bifurcación." He attributes the expression "empate catastrófico" to Gramsci.

The "empate" (blockage, standoff, deadlock, or impasse), as García Linera uses the concept, appears to refer to Gramsci's use of the concept of "equilibrium," often conjoined with the adjective "catastrophic," in his Prison Notebooks; it denotes a sort of stasis in the configuration of the class struggle, when neither of the major contending class blocs has the ability to establish its hegemony over the other, a situation that can endure (as García Linera says) for months or even years. See also the interview with García Linera in the Argentine on-line periodical Renacer: "Del empate catastrófico al desempate conflictivo."

Suggestions for further reading: "Neo-liberalism and the New Socialism -- Speech by Alvaro Garcia Linera," Political Affairs, January-February 2007; and Álvaro García Linera and Jeffery R. Webber, "Marxism and Indigenism in Bolivia: A Dialectic of Dialogue and Conflict," ZNet, April 25, 2005

_DCE.jpg)

Comment by Felipe Stuart

The months that have passed since the speech was first delivered resonate with examples of the theoretical generalizations that García Linera makes. It is a forceful contribution to our understanding of unfolding struggle in his landlocked country.

The problem of hegemony and relationship of forces, and points of

bifurcation that García Linera outlines have relevance for our current struggle in Nicaragua (always keeping in mind of course that every country presents these problems in unique and very concrete ways, and often in ways that are counterintuitive. It is therefore risky to directly extrapolate general processes from one country and apply them to another. Nevertheless, on a less fine-grained level one can’t help but see some lessons from García Linera for understanding Nicaraguan events since the 1990 electoral defeat.

That defeat of the FSLN in 1990 was more a referendum on war that a rejection of the goals of the revolution. Of course it was a historic defeat for the only course that could take the revolution forward. However, the question of the relationship of forces remained unresolved on many levels. The armed forces remained Sandinista.

As it turned out, the country could only be governed by three subsequent neo-liberal presidencies making deals with the FSLN leadership (governability, anyone?). For the entire period since the 1990 elections no one party has been able to govern without negotiating fundamental issues with the opposition. That remains true today, with the FSLN managing a minority government through an arrangement with the PLC called "the pact."

The first pact during this period was between the government of Violeta Barrios de Chamorro and the FSLN. It was arranged from the FSLN side by Sandinista Army General (now retired) Humberto Oretga and former Sandinista Vice-president Sergio Ramirez. This pact led to a crisis in the FSLN, and the organization of the Democratic Left tendency in the party, led by Mónica Baltodano, Victor Hugo Tinoco, and other compas (comrades). Daniel Ortega came on side by the time of the 1994 Congress, and these forces defeated the right-wing current led by Sergio Ramirez and Dora Maria Tellez (I was active in the Democratic Left current and well recall the Congress victory over the "pact makers" who now lead the MRS). Upon their defeat the vast majority of this right wing current, including the overwhelming majority of FSLN deputies in the National Assembly, split away and formed the social democratic Sandinista Renovation Movement (MRS).

Subsequently the FSLN, with Daniel Ortega by then back at the helm, formed a pact with the PLC (Liberal Constructional Party [headed by former president, Arnoldo Alemán). At first the FSLN participated in the pact from its position as an opposition party to two different Liberal presidents. Now in office as a minority government, the FSLN has continued this arrangement with the PLC, in order to be able to pass legislation in the Legislature. The longevity of this “special arrangement” has led not a few to fear that a bi-partisan structure will evolve in Nicaraguan politics where only the FSLN or the PLC will be able to capture significant support. That has actually been the situation since at least 1996.

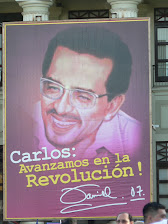

The reality in Nicaragua is that there are two competing hegemonies in terms of electoral politics. On the ideological level the country is still under the domination of neo-liberal concepts and perspectives. Only a minority of the population identify with the original goals of Carlos Fonseca and the FSLN, but a significant minority, waiting to be called to action. There are also important generational gaps. No polls, to my knowledge, exist to verify where youth stand on broader ideological issues; however, my reading is that a majority of youth are bound to pro capitalist notions, but without pro-imperialist leanings. Only ongoing struggles can win the youth to a revolutionary nationalist and anti-capitalist perspective, or rather to the historic program of the FSLN. This must be developed through advancing a program based on concrete demands and proposals that expose the historic inability of capitalist solutions to the country’s impoverishment and imperialist domination. The FSLN government has brought to an end the nation’s semi-protectorate status, but that advance could easily be reversed if the FSLN loses the next national elections. What it cannot accomplish, if it remains trapped in the constraints of an imperialist-dominated economy, is genuine national liberation. That prospect must take the country deeper into the process of regional alliances with countries sharing the same goals, such as Bolivarian Venezuela, Ecuador, and Bolivia. Ultimately the question of hegemony in Nicaragua can only be resolved on a regional scale and within the framework of a changing international relationship of forces.

The big difference between the Nicaraguan situation and the Bolivian is that the MAS government came to power as the result of a series of ongoing mobilizations prior to its electoral victory. Coupled with the revolutionary nature of the process in Bolivia is the establishment of indigenous majority rule, now under sharp and dangerous challenge from the oligarchy, mainly based in the eastern "Media Luna" part of the county. The Nicaraguan process lacks the factor of mobilization of the masses. Prior to the 1996 election victory, the FSLN acted to hold its base within an electoral framework and effectively demobilized the party ranks. This is now beginning to change through the formation of the Citizens’ Power Councils (CPCs) that are working at the barrio and district levels in cities, towns and rural areas of the country. The mass base of the FSLN in the CPCs, the unions, the student movement, and small and medium-size producers could be brought into the streets rapidly if efforts to topple the Ortega government become stronger or threatening.

We saw a demonstration of the scope, density, and power of this base in the few days immediately following the November 2006 election. Tens of thousands of people took to the streets and stayed there until it became clear that the USA would accept their party’s victory. The only possible way Daniel Ortega could continue to govern, if the rightwing succeed in uniting their forces in an attempt to checkmate the government, will be to lead a counter mobilization of the Sandinista masses.

This problem would likely lead to important sectors of the oligarchy and the US State Department to reconsider their options. A mobilization of the Sandinista base could be very dangerous for them. It could only occur around a program a radical demands against the privileges of the rich (radical tax reform, repudiation of a major part of the internal debt that resulted from a banking scam nearly a decade ago, and so on).

The above is only a thumbnail sketch of some of the problems of power relations at the political level in Nicaragua. I find that the García Linera article develops a set of concepts that could, with proper sense of proportion and relevance, be of great utility in analyzing class and national struggles in many countries of Indo-Black-Latin America. I should mention, as well, that the Bolivian V.P. García Linera has had occasion more recently to present talks and articles that describe the ongoing standoff between the oligarchy and the MAS government in more concrete terms. Let’s hope he keeps providing Bolivia’s popular movements and international supporters with his incisive analyses.

Felipe Stuart C.

Managua

No comments:

Post a Comment