My last post also dealt with the topic of the continental upsurge of the indigenous movement for self-determination and liberation from the yoke of centuries of capitalist oppression brought on by the European conquest.

This article not only has greater depth, but also has a more ambitious goal – to present and discuss many of the political and strategic issues under debate in the movement up and down our hemisphere.

While I do not fully share all of the positions advanced by the author, I have no doubt that this is a valuable contribution and addition to the arsenal of critical analysis of the movement and the challenges it faces.

Felipe Stuart

Managua

The article is taken from:

http://americas.irc-online.org/am/5020?utm_source=streamsend&utm_medium=email&utm_content=312932&utm_campaign=%5BAmericas%20Updater%5D%20Must-read%20Mexico%20Blog%2C%20North%20America%20Myths%2C%20Mapuche%20Victory%2C%20Indigenous%20Autonomies

Francisco López Bárcenas

February 26, 2008

Translated from: Autonomías Indígenas en América: de la demanda de reconocimiento a su construcción

Translated by: Maria Roof

Americas Program, Center for International Policy (CIP) americas.irc-online.org

"In the struggle for a freed Latin America, in opposition to the obedient voices of those who usurp its official representation, there arises now, with invincible power, the genuine voice of the people, a voice that rises from the depths of its tin and coal mines, from its factories and sugar mills, from its feudal lands, where obedient to usurpers of their official function, now rises with invincible power, the genuine voice of the masses of people, a voice that emerges from the bowels of coal and tin mines, from factories and sugarcane fields, from the feudalistic lands where rotos, cholos, gauchos, jíbaros, heirs of Zapata and Sandino, grip the weapons of their freedom."

—Havana Declaration, 1960

Latin America is living a time of autonomy movements, especially for indigenous autonomy. The demand became a central concern in national indigenous movements in the 1990s and intensified in the early 21st century.

Not that it didn't exist before. On the contrary, demands for autonomy have permeated struggles of resistance and emancipation by indigenous peoples since the conquest—Spanish in some cases, Portuguese in others—and the establishment of nation-states, since the rebellions against colonial power by Tupac Amaru, Tupac Katari, and Bartolina Sisa in the Andes and Jacinto Canek in Mayan lands; by Willka Pablo Zarate in Bolivia, and Tetabiate and Juan Banderas among the Yaquis in Mexico during the republican period [1800s]; Emiliano Zapata in Mexico and Manuel Quintín Lame in Colombia in the 20th century; and on into the 20th and 21st centuries with the Zapatista rebellion in Mayan areas.

These struggles have included among their most important demands the same utopian proposals that arise from peoples demanding full rights, territories, natural resources, self-defined organizational methods and political representation before state entities, exercise of internal justice based on their own law, conservation and evolution of their cultures, and elaboration and implementation of their own development plans.

This is not a small matter. From the beginning of the 21st century, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) warned that indigenous movements would be one of the main challenges to national governments over the following 15 years and that they would "increase, facilitated by transnational networks of indigenous rights activists and supported by well-funded international human rights and environmental groups. Tensions will intensify in the area from Mexico through the Amazon region ... ."1

More recently, United States Deputy Secretary of State, John Dimitri Negroponte, referring to victory by the indigenous Aymara Evo Morales Ayma in the Bolivian presidential elections, averred that subversive movements are misusing the benefits of democracy, which endangers the stability of nation-states throughout Latin America.

Indigenous movements and their struggle for autonomy are a concern for dominant economic and political groups because they are a part of other social movements in Latin America that are resisting neoliberal policies and their effects on people. They are also an integral part of the broad social sectors supporting alternative proposals that would help us resolve the crisis in which the world finds itself.

But in contrast to others, indigenous peoples movements and organizations are more radical and deeper in their framing of the issues, as is apparent in their choice of the means of struggle—mostly pacific, but when that is not possible, with the use of violence—and also because their demands require a profound transformation of national states and institutions that would practically lead us to a re-founding of nation-states in Latin America.

The reclamation by indigenous peoples of recognition of their autonomy has another component that gives pause to the hegemonic classes wielding power in Latin American states where movements occur. Movements arise precisely at a time when states begin to undergo a serious weakening, a product of the push by international economic forces to move them out of the public sphere and reduce them in practice to simple managers of capitalistic interests.

Paradoxically, these same classes scream to high heaven that states will fall apart if the indigenous peoples' demands are met—demands for reformation or re-founding of states to make them more functional for the multiculturalism of their populations. But the reality is quite different, because if a new state were established with indigenous peoples recognized as autonomous political subjects, surely it would be strengthened, and then free market economic forces would lose their hegemony in the crafting of anti-popular policies.

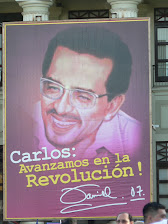

This argument has been used by those in power to design counterinsurgency policies against social movements and their allies, under the guise of defense of national sovereignty, as has happened in different ways. In some cases, for example, Bolivia and Mexico, the state directly confronted the indigenous movements, even mobilizing its military without respecting the constitution. In other places like Panama and Nicaragua, and to a certain extent in Ecuador, especially in the Andean region, the use of an "encircling strategy" has been adopted in order to recover lost spaces.

In these cases there is no violent confrontation, because political parties are used as a means of control, offering channels to power that become forms of control and disarticulation. Another strategy is isolation, used in Brazil and part of Ecuador, where an open field has been left for transnational companies exploiting natural resources to directly confront indigenous discontent, while the state acts as if nothing were happening.2

Let's be clear: indigenous peoples in Latin America struggle for autonomy because in the 21st century, they are still colonies. The 19th-century wars for independence ended foreign colonization—Spanish and Portuguese, but those who rose to power continued to view indigenous peoples as colonies. The hegemonic classes hid these colonies behind the mask of individual rights and juridical equality, proclaimed by that century's liberalism, and now, given proof of the falsity of that argument, they hide behind the discourse of conservative multiculturalism, apparent in legal reforms that recognize cultural differences in the population, although the state continues to act as if they did not exist.

Meanwhile, Latin American indigenous peoples suffered and continue to suffer from the power of internal colonialism. That is why indigenous movements, in contrast to other types of social movements, are struggles of resistance and emancipation. That is why their demands coalesce in the struggle for autonomy; that is why the concern among imperialist forces increases as the movements grow; that is why achievement of their demands implies the re-founding of national states.

500 Years of Resistance

In 1992, indigenous movements substantively revised their forms of political actions and their demands in the context of the continental campaign of 500 years of indigenous, black, and popular resistance, in which different indigenous movements on the American continent protested against government-supported celebrations of five centuries since the European invasion, or so-called "discovery."

First, indigenous movements ceased to be appendices to rural farmer movements, which had always put them last in their participation as well as their reclamations, and became political subjects themselves. Then, they denounced the internal colonialism exercised against them in the nation-states where they lived, revealed "indigenism" as a policy to mask their colonial situation, and demanded their right to self-determination as the peoples that they are.

Nicaragua is an exceptional case because, after the counterrevolution adopted ethnic discourse, it established regional autonomies in 1987 in order to deactivate the armed opposition, and this, over time, also effectively deactivated the indigenous movement. Except for this case, since 1992 indigenous movements are movements of resistance and emancipation: resistance in order to not cease to be peoples; emancipation in order to not continue being colonies. Ethnic reclamations were conjoined with class reclamations.

The axis of the indigenous movements' demands became the right to free determination expressed in autonomy.

Since 1966, the UN Pacts on Civil and Political Rights and on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights recognized peoples' right to free determination and, as a result, to freely establish their political condition, as well as make decisions about their economic, social, and cultural development. The recognized right included the free administration of natural resources for their own benefit, without ignoring the necessity of international cooperation based on mutual benefit.

Indigenous movements demand not only rights for individuals but also for collectives, for the peoples they are part of. Their demand is not limited to making state institutions fulfill their functions but also change. They demand not lands but territories. They ask not that they be allowed to exploit the natural resources in their territories, but that they be granted ownership of them. They demand that justice be administered not only according to state law, but also in recognition of their right to administer justice themselves and in accordance with their own laws. They seek not development plans designed for them, but recognition of their right to direct their own development. They want their own cultures recognized and respected instead of only the dominant culture. Indigenous peoples do not want to continue as colonies, but rather, as peoples with full rights.

These reclamations by indigenous movements opened a new period in the history of indigenous rights, which first became visible when Latin American nation-states that had not already revised their political constitutions and internal legislation to incorporate recognition of indigenous peoples and guarantee their collective rights, did so. A legislative fever was unleashed, but legislation was passed so that the political class would not lose legitimacy, more than to recognize rights. In this way, except for a few places like Chile, almost all states revised their political constitutions to incorporate indigenous peoples and their rights.

Autonomous Tendencies

When indigenous peoples realized that their struggle for constitutional recognition of their rights had not produced the desired results, they focused their efforts on building de facto autonomies. Some movements that already had shifted in this direction grew more powerful, as others began the long path of making the shift. To accomplish this, they appealed to what they had: their cultures, histories of resistance, organic structures, relations with other social movements, and concrete realities in their countries.

On different levels during the 1990s, Latin American states noticed transformations in the indigenous movements that had struggled since the prior decade to reclaim their rights. Some movements transcended local struggles and broke national barriers, achieving more notoriety than others. Indigenous movements for autonomy were a social phenomenon seen in all of Latin America. Just when worker and rural farmer movements were weakening from Mesoamerica to Patagonia, indigenous movements were reactivating, much to the concern of neoliberals.

Community-based autonomies arose as a concrete expression of indigenous peoples' resistance to colonialism and their struggle for emancipation. Since the majority of indigenous peoples were politically de-structured, and communities were the concrete expression of their existence, when indigenous movements propelled the struggle for their self-determination as peoples, it was the communities that defended the right. To do this, they used their centuries-old experience in resistance, but also their self-generative experiences within the farm workers movement.

Entrenched in community structures, indigenous movements forcefully made themselves heard, and in many cases, states had no alternative other than yielding to their demands. The strongest proof of this is that most Latin American legislation on indigenous rights recognizes the juridical personhood of indigenous communities and enunciates some of the competencies states recognize in them, all the while requiring, as stated in the recognitions, their conformity to the framework of state law.

Another tendency among indigenous autonomies is the regional autonomy proposal. It arose in response to the need to surpass the community space of indigenous peoples and seek spaces not only larger than the community, but also beyond local state governments. Its first expression was in the autonomous regions in Nicaragua, introduced as a form of government in the 1987 Political Constitution of the State. Since this event, unprecedented in Latin America, it spread to other countries through intellectuals close to indigenous reclamations, to the extent that in some countries, such as Mexico and Chile,3 proposals were put forth for constitutional reforms and statutes of autonomy. In others, it remained one more tendency in the struggle for indigenous autonomy but without any concrete expression.

As on many other occasions, indigenous movements themselves resolved the "contradiction" between community proponents and regionalists. When the occasion presented itself, first they showed that the proposals were not contradictory, but rather, complementary. This has been very clear in Mexico with the Zapatista Caracoles communities, but also in the community police in the state of Guerrero.

The same is happening in the Cauca region of Colombia and in the Cochabamba Department in Bolivia. In all these cases it has been demonstrated that communities function as a foundation for building regional structure, which is the roof for autonomy, and they can combine effectively, because regional autonomy is not imposed from above, but occurs as a process that consolidates the communal autonomies that then decide the scope of the region.

Together with the community and regional tendencies there are other indigenous movements that do not demand autonomies but the re-founding of nation-states based on indigenous cultures. This is the tendency most apparent in the various movements in the Andean region of the continent, especially among the Aymara in Bolivia. Participants in these movements say they do not understand why, since their population is larger than the mestizos, they should adapt to the political will of minorities.

Many Latin American governments have coopted the indigenous movement's discourse, emptied it of meaning, and begun to speak of a "new relationship between the indigenous peoples and the government," and to elaborate "transversal policies" with the participation of all interested parties, when in reality they continue to posit the same old indigenist programs that indigenous peoples reject.

In order to legitimize their discourse and actions, they have incorporated into public administration a few indigenous leaders who had long worked for autonomy and now serve as a screen to depict as change what actually is continuity. Some countries have gone further by denaturing the autonomy demand and presenting it as a mechanism by which certain privileged sectors maintain their privileges. This is the case among the bourgeoisies in the departments of Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia, Guayaquil, Ecuador, and the state of Zilia in Venezuela.

If one assumes that autonomy is a concrete expression of the right to free determination, and that this is a right held by peoples, it cannot be forgotten that the titular subjects of indigenous rights are the indigenous peoples, not their communities, much less the organizations that they build to propel their struggle. This is why along with building autonomies, indigenous movements assume a commitment to their own reconstitution. At this particular juncture, given the fragmentation among the majority of indigenous peoples, communities are important to articulate their resistance struggles and building of autonomies, but movements do not renounce the utopia of reconstituting the indigenous peoples of which they are a part, so that the peoples can assume the holdership of rights. For this reason the defense of community rights is made at the same time as they establish relations with other communities and peoples in their countries and elsewhere, to support each other in their particular demands, but also hoist common demands.

An external problem to becoming political subjects encountered by indigenous peoples is that in the majority of cases, they are politically de-structured, affected by the politics of colonialism wielded through government entities in order to subject them to the interests of the class in power. A concrete example of such politics is that numerically larger indigenous peoples find themselves divided between various states or departments, and the smaller ones between different towns, municipalities, or mayoralties, depending on how states organize local governments.

Indigenous peoples know that in this situation the construction of autonomies can rarely be done from those spaces, because even if they were in control of local governments, their structure and functioning would follow state logic, limiting their faculties to those that are functional to state control; but in the worst of the cases it could turn out that, in the name of indigenous rights, power is handed over to the mestizo groups led by local cacique bosses, that would use it against indigenous peoples.

On the other hand, they know that indigenous communities composed of one people find themselves divided and in conflict for diverse reasons that run from land ownership, use of natural resources, and religious beliefs, to political preferences, among others. In other cases fictitious or invented problems are created by actors outside the communities.

To confront these problems interested indigenous peoples make efforts to identify the causes for division and conflict, locate those that originate in the communities' own problems, and seek solutions. At the same time, they try to determine problems created from the outside and seek ways to repulse them.

The struggle for the installation of autonomous indigenous governments represents an effort by indigenous peoples themselves to construct political regimes different from the current ones, where they and the communities that form them can organize their own governments, with specific faculties and competencies regarding their internal life.

With the decision to build autonomies, indigenous peoples seek to disperse power in order to achieve its direct exercise by the indigenous communities that demand it. It is a sort of decentralization that has nothing to do with that pushed by the government with the support of international institutions, which actually endeavors to enhance government control over society. The decentralization we are talking about, the one that indigenous peoples and communities advancing toward autonomy are showing us, includes the creation of paralegal forms to exercise power that are different from government entities, where communities can strengthen themselves and make their own decisions.

When indigenous peoples decide to build autonomies, they have made a decision that goes against state policies and forces those who choose that path to begin political processes to build networks of power capable of withstanding state attack, counter-powers that will allow them to establish themselves as a force with which governance must be negotiated, and alternative powers that will oblige the state to take them into account. This is why building autonomies cannot be a volunteerist act by "enlightened" leaders or an organization, no matter how indigenous it claims to be.

In any case, it requires the direct participation of indigenous communities in the processes toward autonomy. In other words, indigenous communities must become political subjects with capacity and desire to fight for their collective rights, must understand the social, economic, political, and cultural reality in which they are immersed, as well as the various factors that contribute to their subordination and those that can be used to transcend that situation in such a way that they can take a position on their actions.

With the struggle for autonomy indigenous peoples and communities transcend the folkloric, culturalist, and developmentalist visions that the state propagates, and many people still passively accept. Experience has taught them that it is not enough for some law to recognize their existence and a few rights not in conflict with neoliberal policies, or cultural contributions by indigenous peoples to the multicultural make-up of the country. Nor is it sufficient for governments to mark specific funds for development projects in indigenous regions, amounts that are always too small and are applied in activities and forms decided by the government, which rob the communities of any type of decision-making power and deny their autonomy.

Is it not by chance that the Zapatista rebellion in Mexico began in January 1994, when the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) between that country, the United States, and Canada went into effect, or that most of the national demands by indigenous movements include the rescue of natural resources from control by transnational corporations, or that the struggles in Ecuador, Peru, and Chile include opposition to free trade agreements.

They also know that the struggle for autonomy cannot be a struggle by indigenous peoples alone. For this reason, they build relations of solidarity with other social sectors, supporting each other in their particular struggles, while at the same time pushing common demands.

Indigenous peoples, by appealing to their culture and identifying practices in order to mobilize in defense of their rights, are questioning vertical political forms even as they offer horizontal forms that work for them, because they have tested them over centuries of resistance to colonialism. These are practices that come into play precisely at a moment when traditional organizations of political parties, syndicates, or others that are class-based and representative, are entering into a crisis, and society no longer sees itself reflected in them.

These political practices are apparent in many ways, from the postmodern guerrilla, as the Zapatista Army of National Liberation has been labeled, that rose up in armed rebellion in 1994 in Mayan lands, brandishing arms more as a symbol of resistance than to make war, to the long marches by authorities among indigenous peoples in Colombia, the "uprisings" of Ecuadoran peoples, or the Aymara blockade of La Paz, Bolivia, and the Mapuche direct confrontation against forestry companies trying to steal their natural resources.

In these battles indigenous peoples, instead of turning to sophisticated political theories to prepare their discourses, recover historical memory to ground their demands and political practices, and this gives the new movements a distinctive and even symbolic touch. Indigenous peoples in Mexico recuperate the memory of Emiliano Zapata, the incorruptible general of the Army of the South during the revolution of 1910-17, whose principal demand was the restitution of native lands usurped by the large landowners. Colombians recuperate the program and deeds of Manuel Quintín Lame. Andeans in Peru, Ecuador, and Bolivia make immediate the rebellions by Tupac Amaru, Tupac Katari, and Bartolina Sisa during colonization, and by Willka Pablo Zarate during the republican period. Local and national heroes are present again in the struggle to guide their armies, as if they had been resting, waiting for the best time to return to the fight.

Along with their historical memory, peoples turn their eye to what they already have so as to become stronger, and, tired of so much disillusionment with traditional political organizations, to recover their own, their own systems of responsibilities. This is why those who are unaware of their particular forms of organization affirm that they act anarchically, that it's not the right way, that they contribute to dispersion, and that it's a bad example for the unity of the oppressed, the exploited, and the excluded.

Final Reflections

Everything said here about indigenous autonomies and the shift from demanding constitutional reform to becoming a process of construction, has as background the search for the root cause of the problem that is the condition of internal colonialism in which indigenous peoples live in the states they are part of.

It is a situation that neither juridical equality of citizens prescribed by 19th-century liberalism, nor indigenist policies imposed by different Latin American states throughout the 20th century, were able to resolve, because they did not go to the heart of the problem which, as can be seen now, involves the recognition of indigenous peoples as collective subjects with rights, but also the re-founding of states to correct the historical anomalies of viewing themselves as monocultural in multicultural societies.

Where will the processes to build indigenous autonomies in Latin America lead us? That is a question that no one can answer, because even the social movements do not know. The actors in this drama draw their utopian horizon, but whether they can achieve it does not depend entirely on them but on different factors, most of which are outside their control. What we can be sure of is that the problem will not be solved in the situation in which states currently find themselves, and for that reason, struggles by indigenous peoples for their autonomy cannot retreat.

Neither the Zapatista guerrilla in Mexico, nor the indigenous self-governments in Colombia, nor the struggles by Andean and Mapuche peoples will find a full solution if the state is not re-founded. But it is also true that states cannot be re-founded without taking seriously their indigenous peoples. The challenge is dual, then: nation-states must be re-founded taking into account their indigenous peoples, and these must include in their utopias the type of state they need and fight for it. This is what indigenous autonomies and struggles to build them are about.

Therefore, we must celebrate that many indigenous peoples and communities have decided not to wait passively for changes to come from the outside and have enlisted in the construction of autonomous governments, unleashing processes where they test new forms of understanding rights, imagine other ways to exercise power, and create other types of citizenships.

No one knows how the processes will turn out, but it is certain that there is no going back to the past.

End Notes

Jim Cason and David Brooks, "Movimientos indígenas, principales retos para AL en el futuro: CIA," La Jornada (Mexico), Dec. 19, 2000, http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2000/12/19/024n1mun.html. The complete English version of the report is posted at: http://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/globaltrends2015/index.html#link2.

Leo Gabriel and Gilberto López y Rivas, ed., Autonomías indígenas en América Latina. Nuevas formas de convivencia política, Plaza y Valdez editores-Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Unidad Iztapalapa-Ludwig Boltzmann Institut, México, 2005, p. 19.

Javier Lavanchy, Conflicto y propuesta de autonomía mapuche, Santiago de Chile, Junio de 1999, Proyecto de documentación Ñuke Mapu, http://www.soc.uu.se/mapuche.

Translated for the Americas Program by Maria Roof.

Francisco López Bárcenas is a Mixtec lawyer, specialist in indigenous rights, and analyst for the Americas Program (www.americaspolicy.org). He is author of Muerte sin fin: crónicas de represión en la Región Mixteca oaxaqueña [Endless Death: Chronicles of Repression in the Oaxacan Mixtec Region] and other books.