Managua, Nicaragua

NB: This article first appeared on the site of foodforethought at http://foodforethought.net/By_Phil_Stuart_Cournoyer%5B1%5D.pdf

It was also posted the next day on the Global South list of York University by a member of that list.

The editors emphasized in their headline and introduction the issue of cheap food imports into the industrially overdeveloped countries. I would have put a different slant on that, emphasizing cheap, slave labor in the semi colonies as the root source of the problem, coupled with the cheap conditions of exploitation (minimal taxes, no environmental controls, no accountability, zero responsibility for injured workers or their health problems, and so on).

But their half full glass, was as I see it half empty.

Ni modo.¡Aye Nicaragua, Nicaraguita!

***

The family of Yolanda Mϋller of Puerto Cabezas, Nicaragua had no cause for joy this Christmas.

Yolanda Mϋller died of cold, hunger, and exhaustion, a long way from her Caribbean Sea home, in a desert near Tucson, Arizona on December 12. She was traveling overland to join her son in Miami, where she hoped to find work. Her seven and nine year old nieces (whom she raised as daughters) accompanied her on the journey, which began on October 25. Suspecting that their mother-aunt was nearly dead, the two girls wandered for hours in the cold and rain looking for help until finally captured by a U.S. border patrol.

The girls related to authorities a horror story that went from bad to worse after the men hired to escort them illegally into the U.S. from Mexico – the coyotes – abandoned them. Getting to the U.S.-Mexico border had also been arduous. The trio spent seventeen days in Managua, seeking a way north. They were delayed 18 days in Guatemala. The trip through Mexico took ten days. At every point on the way they were completely dependent on coyotes and their agents who traffic in and prey on desperate people forced into illegal migration by economic necessity.

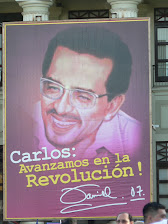

Yolanda’s husband, Zoilo Carrasco, says that his wife decided to go to Miami to find work in order to help pay off a huge debt owed to local loan sharks in her home town. Since 1990 – the year of the defeat of the Sandinista Popular Revolution and government - over one million Nicaraguans (well over 20% of the population) have left the country in search of work. About half of them ended up in the United States, many of them illegally. Once there, they are subject to harassment and deportation, and are forced into lowly-paid, menial and dangerous jobs.

Costa Rica is the main regional destination of Nicaraguan emigrants, followed by El Salvador and Mexico. Most end up as harvest workers or domestics (most domestics in Costa Rica are young Nicaraguan women and girls). A construction boom in Costa Rica is also attracting foreign skilled workers, with some 40,000 Nicaraguan job applicants now on waiting lists to be processed by that country’s immigration officials.

Nicaraguan “illegals” and also documented workers in Costa Rica are subject to many abuses. This ongoing problem is a source of friction and diplomatic strife between the two countries. The long history of exploitation and abuse of Nicaraguan workers, especially of women domestics and harvest workers, has spawned strong racist and xenophobic prejudices against “Nicas.”

Roundups and expulsions of undocumented workers are common. These often ugly and painful experiences involve official abuse, separation of children from parents and relatives, theft of belongings, and worse.

A January 14 report in the Managua daily El Nuevo Diario describes the typical treatment of "illegals” when they are picked up by the Costa Rican “migra.”

One worker relates that: “The Tico [Costa Rican] guards caught us and tied us up. They forced us to lie face down on the ground and kicked us in the ribs. Then they had us stand facing a wall and forced us to strip completely naked, under pants and all. They aimed guns at us and verbally abused us before taking us off to the detention center.”

Another worker described the same treatment and repeated some of the offending comments from the guards: “Nica bastards,” “pigs,” “grasshoppers,” “thieves,” “sloths.” The guards usually steal whatever they find of value in the belongings of their captives, and then place them in filthy, unhygienic detention cells until they are deported.

Rural workers’ roundups and deportations often occur just before pay days – a primitive form of lowering the cost of labor that can only be called slavery. Many of the harvest workers are victims of pesticide poisoning and worksite accidents, but lack the right to access health and social programs in the “host” country.

Hundreds of Nicaraguan banana workers and family members who are slowly dying from the DBCP nematicide (nemagon) exposure are still waiting for justice, despite both Nicaraguan and California court decisions ordering the Dole food giant and Dow Chemical Co. to compensate them. Dole and other US corporations used DBCP-based pesticides in Costa Rica, Honduras, and Nicaragua in the 1970s and 80s, although Dow had stopped marketing it previously in the US because of proven hazards to human health.

Nicaraguan women domestics in Costa Rica work long hours and are lucky if they have one day off a week. Many are subject to sexual abuse and rape by the “man of the house” or his adult sons.

The experience of Nicaraguan migrant labor is not unique.

A December 27 New York Times article by Jason DeParle - A Global Trek to Poor Nations, From Poorer Ones – looks at the growing trend of “south-south” migration [ http://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/27/world/americas/27migration.html?_r=1&th&emc=th&oref=slogin ].

De Parle writes: “There are 74 million ‘south to south’ migrants, according to the World Bank, which uses the term to describe anyone moving from one developing country to another, regardless of geography. The bank estimates that they send home $18 billion to $55 billion a year. (The bank also estimates that 82 million migrants have moved "south to north," or from poor countries to rich ones.)

“Nicaraguans build Costa Rican buildings. Paraguayans pick Argentine crops. Nepalis dig Indian mines. Indonesians clean Malaysian homes. Farm hands from Burkina Faso tend the fields in Ivory Coast. Some save for more expensive journeys north, while others find the move from one poor land to another all they will ever afford. With rich countries tightening their borders, migration within the developing world is likely to grow.”

“‘South to south migration is not only huge, it reaches a different class of people,’ said Patricia Weiss Fagen, a researcher at Georgetown University. ‘These are very, very poor people sending money to even poorer people and they often reach very rural areas where most remittances don't go’.”

The Nicaraguan case is typical of both south-south migration and south-north migration. It is also a country with significant internal migration caused in the 80s by the US-Contra war against the revolutionary government and people, and in the 90s by the collapse of small-scale farming because of conscious neo-liberal policies to destroy the Sandinista agrarian reform. Unemployed and landless rural folks emigrate to the shantytowns around the larger cities, especially Leon and Managua, but also Chinandega, Matagalpa, Estelí, and Granada. Family remittances sent home to Nicaragua by emigrant workers now account for the second most important source of hard currency (in El Salvador's case it is the largest source).

In his recent study Megacapitales de Nicaragua (Ediciones Albertus, 2007), the economist Francisco J. Mayorga (the first minister of economy following the restoration of U.S. domination after the 1990 FSLN electoral defeat) describes the accumulation process as a social pyramid with the emigrant workers on the bottom acting as a major source of capital accumulation.

He writes, "Meanwhile, at the base of the social pyramid, and as a result of the same neo-liberal policies that sparked the rise of mega capital, the levels of unemployment and poverty have been increasing. As a result, many Nicaraguans emigrate each year in greater and greater numbers, assuring a growing flow of family remittances, the main substrata of the market on which mega capital is germinated. "Due to these four processes - emigration, remittances, germination of mega capital, and transnationalization of the economy [this refers to the regionalization of investment whereby the local capitalists lose their national character and locate a significant share of their investments in other Central American countries, and in Mexico, and also in industrially advanced countries.] Nicaragua is changing rapidly: a new development pattern is in gestation. A new economic and social structure is being modeled, much more asymmetric than in the past. In summary, Nicaraguan society is evolving towards new social dynamics and a new distribution of power” [translated from Spanish by PSC].

Central to Mayorga’s argument is that the Nicaraguan capitalist sector consciously promotes the export of young workers because family remittances are a major pool of wealth that they tap in their accumulation process. An important slice of that wealth ends up in their hands after, of course, U.S. capital has taken the lion's share. The phenomenon of worker emigration is but another form of pillage of poor, semi colonial countries. It robs them of potential human capital represented in the brains and skills of those workers. Many of the best educated youth in Nicaragua end up emigrating to the U.S.A. The population exodus largely drains the rural areas of human resources – farmers and workers who would be essential to any sustainable program of national or regional food self-sufficiency. Food self-sufficiency can only be attained through revitalizing small farming and reducing the weight of large-scale, export-oriented monoculture such as coffee, banana, sugar, and corn destined not for tortillas but for ethanol production and export.

The rapid growth of the volume of family remittances has led to a whole new field of study and research. Investors, of course, are primarily concerned with how to capture that wealth, as Mayorga described in the Nicaraguan case. But social planners are also eager to understand both the positive and negative impacts of “remittances” on poor countries. In addition to the drain of human capital, so-called “developing” countries are damaged in other ways by the dependencies created by remittances. promote and sustain a culture of living on handouts, of accepting unemployment and parasitism as a way of life. This gives rise to even more alcoholism and drug consumption, to abuse and violence within families, and other related maladies. When migration levels reach such high proportions, the social fabric of the county is frayed, leaving behind intractable problems from a national and regional perspective. Instead of decreasing dependency, the countries exporting such labor to the developed world, or to more “developed” states of the South, end up increasing their dependency and expanding the myriad of ways such dependency inflicts social and economic harm.

It is a tale with no happy ending – not for the workers and children who go off in search of desperate solutions, nor for those left behind.

No comments:

Post a Comment