Many people in Nicaragua, and many Nicaraguan economic exiles in the United States, believe that Barack Obama is the candidate who would best protect their interests in a troubled world.

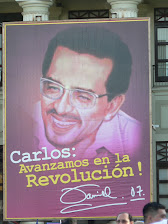

Our president, Daniel Ortega, recently stated that he considers the Obama campaign to have revolutionary potential because of perceived differences between his attitude towards oppressed countries and those of Hillary Clinton, not to speak of the Republican front runner. Ortega also sees the mere fact that a Black man could become president as a revolutionary development in US society.

I have the same kind of reaction every time I see a CNN news broadcast on the primaries and their focus on which horse is ahead. It seems like a nightmare of deception, vote buying, and outright mendacity. No doubt it is all that. But it also seems that massive numbers of oppressed and poor people, and youth, are trying to find in the campaigns signs of a response to their problems. Obama seems to be striking a chord among many of them -- more so that Hillary Clinton.

Not a few Nicaraguan observers have pointed to what they perceive to be an underlying mood of hope that perhaps Obama might make a difference; and among antiracists a hope that if he wins the DP nomination, rednecks in the US will be put on the defensive. One should keep in mind that Nicaraguans have known for a century and more a lot about the racist US culture, and have been its direct victims ever since William Walker attempted to re-impose slavery of Blacks in Nicaragua. Hundreds of thousands of Nicaraguan immigrants toil in the US as super exploited and oppressed laborers, many facing harassment as undocumented, and most experience firsthand skin discrimination, language discrimination, and other forms of oppression.

Angela Davis sees things somewhat differently, and seems to have a much keener appreciation of what is behind these perceptions and moods. I feel indebted to the explanations she offers in this interview with Gary Younge of the Guardian UK -- that is posted here below.

Felipe Stuart

Managua

Gary Younge

The Guardian,

Thursday November 8 2007

http://www.southbankcentre.co.uk/

This article appeared in the Guardian on Thursday November 08 2007 on p10 of the Comment & features section. It was last updated at 10:31 on November 14 2007.

Angela Davis was intrigued to see recently that a significant number of young black women to whom she was delivering a talk were wearing images of her from the 70s on their T-shirts. She asked what the image meant to them. "They said it made them feel powerful and connected to other movements," she says. "It was really quite moving. It really had nothing to do with me. They were using this image as an expression of who they would like to be and what they would like to do. I've given up trying to challenge commodification in that respect. It's an unending battle and you never win any victories."

For all her many achievements over the past 37 years, Angela Davis remains, for many, a symbol frozen in time. The time was 1970. It marked the end of a tumultuous era of civil rights struggle that culminated in the assassination of two of black America's most renowned leaders - Martin Luther King and Malcolm X. A period of peaceful demonstrations for integration in the rural south had been followed by a spate of violent disturbances in the urban north. The focus had shifted from integration to black power; the influences from Gandhi and the Bible to Mao and Marxism. In 1967, Aretha Franklin called for "r-e-s-p-e-c-t"; by 1970, the anthem was Edwin Starr's War.

The symbol was resistance. Smart, handsome, eloquent, fearless and stylish, Davis strode the political stage with her fist raised high and her afro combed even higher. A rebel and a revolutionary. A silhouette for summerwear. Radical and chic like Che - except that she has lived to see her political resistance transfer into popular culture.

A student in her history of Afro-American women's studies class at San Francisco State University during the 80s recalls: "She wanted to teach and she was a very conscientious teacher, really engaging. But she would make some cogent point about history and then someone would literally put up their hand and make some comment about her hair. I thought, 'They're not letting her be who she wants to be.'"

Davis once said: "It is both humiliating and humbling to discover that a single generation after the events that constructed me as a public personality, I am remembered as a hairdo."

A few weeks ago, at the Women of Colour Resource Centre in Oakland, California, Davis presented the Sister of Fire award to a young poet from Queens in New York who could barely contain her excitement at being in her presence. "I can't believe I'm on the same stage as Angela Davis," she gushed. "I read about her in school ... And she's still alive." Davis and her contemporaries at the ceremony laughed.

"I have reconciled myself to the existence of this historical figure and its relationship to the work that I'm trying to do today," she says. This is less difficult than it might seem since her present work is intricately connected to both the work she has been doing most of her adult life and the incident that made her famous: prisons.

Back in the 60s, as the American state moved to criminalise radical black protest, she primarily campaigned on the issue of political prisoners such as the Black Panther George Jackson. Her political activities had already made her a target for the conservative establishment. In 1969, she was fired from her job as assistant professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, for being a member of the Communist party, only to see that decision overturned by a supreme court judge.

Then, on August 7 1970, her own infamous run-in with the criminal justice system started. On that day, Jonathan Jackson, 17, held the Marin county courthouse at gunpoint and sprung three prisoners - James McClain, William Christmas and Ruchell Magee - who were either witnesses or on trial. The men led the judge, Harold Haley, the prosecuting attorney and some jurors to a waiting van and fled. In the ensuing chase, Jackson, Christmas, McClain and Haley were shot dead, while the attorney was paralysed by a police bullet.

Jonathan was the younger brother of George Jackson, whom Davis had fallen in love with during the campaign for his release. Jonathan's gun was registered in Davis's name. Davis was nowhere near the shoot-out, but a warrant was issued for her arrest, for conspiracy to kidnapping and murder. She went on the run.

Davis's disappearance sparked an intensive, public search and propelled her to the FBI's top 10 most wanted, and to international attention. Two months later, she was arrested in a motel in mid-town Manhattan.

President Richard Nixon branded her a "terrorist". Facing the trinity of rightwing hate figures - Nixon, the then California governor Ronald Reagan and FBI director J Edgar Hoover - Davis became an international cause celebre. A global campaign called for her release. Aretha Franklin offered to post quarter of a million dollars in bail. "I have the money," she said. "I got it from black people and I want to use it in ways that will help our people."

In January 1971, Davis appeared in Marin county court, unapologetic and defiant, facing charges that could have lead to her execution. A year and a half later, an all-white jury acquitted her. As an academic of great renown, she went on to enter the canons of black and feminist theory with her books - on women, on race and class and women, on culture and politics. She wrote a bestselling autobiography and stood for vice-president in 1980 and 1984 on the Communist party ticket.

Much has changed in her life since the days of her trial but a great deal has remained the same. Davis still teaches at the University of California - although now at Santa Cruz, where she is professor of history of consciousness and feminist studies. At 63, she is still recognisable from those iconic 70s shots, although her hair is now a cascade of corkscrew curls. And her primary focus remains the criminal justice system. According to the US justice department, on current trends, one in three black boys born in 2001 will end up in jail.

"The prison system bears the imprint of slavery perhaps more than any other institution," she says. "It produces a state that is very similar to slavery; the deprivation of rights, civil death and disenfranchisement. Under slavery, black people became that against which the notion of freedom was defined. White people knew they were free because they could point to the people who weren't free. Now we know we're free because we're not in prison. People continue to suffer civil death even after they leave prison. There is permanent disenfranchisement."

The US, argues Davis, is still struggling with its refusal to address slavery's legacy. "There was the negative abolition of slavery - the breaking of chains - but freedom is much more than just the abolition of slavery. What would it have meant to provide economic security to everyone who had been enslaved; to have brought about the participation in governance and politics and access to education? That didn't happen. We are still confronted by the failure of the affirmative side of abolition all these years later."

Does that not leave black politics entrenched in a paradigm set almost 150 years ago? "The problem is that we [as a country] haven't moved on," she says. "Certainly it's important to recognise the victories that have been won. Racism is not exactly the same now as it was then. But there were issues that were never addressed and now present themselves in different manifestations today. You only move on if you resolve these issues. It took 100 years to get the right to vote."

Born in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1944, Davis was raised in the tightknit world of the black middle class in a small southern town. It included the families of secretary of state Condoleezza Rice and Alma Johnson, who would later marry former secretary of state Colin Powell.

Davis was seven years younger than Johnson and 10 years older than Rice. Their worlds intertwined but never quite collided. Rice's father, John Wesley Rice Jr, worked for Johnson's uncle as a high-school guidance counsellor. Johnson knew Rice as a child; Davis knew Johnson, because they attended the same church. Birmingham became notorious during the 60s as the town that set dogs and hoses on African-Americans seeking the vote, and for the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist church, in which four little girls were killed in 1963, one of whom was Rice's friend. Its reputation was so bad that Colin Powell's parents considered not going to their son's wedding and joked about the likelihood that they would be lynched when they got there.

Although all three emerged from that time and place to take advantage of the new opportunities available, Davis's perspective on her achievements could not be more different to Rice's. "In America, with education and hard work it really does not matter where you come from," Rice told the Republican convention in 2000. "It matters only where you are going."

She later told the Washington Post: "My parents were very strategic. I was going to be so well prepared, and I was going to do all of these things that were revered in white society so well, that I would be armoured somehow from racism. I would be able to confront white society on its own terms."

Davis insists this is disingenuous. "It was never about individuals. I never grew up thinking that the measure of my success was as an individual.

There was always a sense that the measure of your success was to a large part one that was linked to community advancement. Most people weren't going to make it as far as she or I did. She never would have had the opportunities she had without the benefit of the struggles that took place in the 60s. If you can, with conscience, talk about a post-civil rights era, we have to talk about the limitations of civil rights. It produced individual successes but it never produced group successes."

The advancement of the likes of Powell and Rice within the Bush administration, argues Davis, exemplifies a flawed understanding of what it means to tackle modern-day racism. "The Republican administration is the most diverse in history. But when the inclusion of black people into the machine of oppression is designed to make that machine work more efficiently, then it does not represent progress at all. We have more black people in more visible and powerful positions. But then we have far more black people who have been pushed down to the bottom of the ladder. When people call for diversity and link it to justice and equality, that's fine. But there's a model of diversity as the difference that makes no difference, the change that brings about no change."

This, she says, is how the presidential candidacy of Barack Obama is generally understood. "He is being consumed as the embodiment of colour blindness. It's the notion that we have moved beyond racism by not taking race into account. That's what makes him conceivable as a presidential candidate. He's become the model of diversity in this period, and what's interesting about his campaign is that it has not sought to invoke engagements with race other than those that have already existed."

Davis's initial response to Obama is one she often gives to questions both specific and general: "It's complicated," she says. Her answers are candid but measured. Not measured necessarily to fit prevailing public opinion - she believes prisons should be abolished, for example - but for their consistency and precision. She talks slowly and in long whole sentences and will often deconstruct the question before replying. Asked about the class stratification in the black community and its implications for black political leadership, she says, "It's complicated. We used to think there was a black community. It was always heterogenous but we were always able to imagine ourselves as part of that community. I would go so far as to say that many middle-class black people have internalised the same racist attitudes to working-class black people as white people have of the black criminal. The young black man with the sagging pants walking down the street is understood as a threat by the black middle class as well. So I don't think it's possible to mobilise black communities in the way it was in the past.

"I don't even know that I would even look for black leadership now. We looked to work with that category because it gave us a sense of hope. But that category assumes a link between race and progressive politics and, as Stuart Hall says, 'There aren't any guarantees.' What's more important than the racial identification of the person is how that person thinks about race."

The confluence of black and progressive politics in the US has been further diminished, argues Davis, as a result of 9/11, which gave all Americans the option of retreating behind the flag or responding to a world that was reaching out. "In that sense, 9/11 was a pivotal moment," she says. "It was a multicultural moment. Black people aren't immune to the nationalism in this country. That was a moment when global solidarity was pouring in and instead of people reaching out, they closed down. So this was a moment that clearly involved black people. But it clearly didn't envelop Arabs."

Black Americans may not have been immune to the hyper-patriotism of recent years, but they were more resistant to it. Of all racial groups, African-Americans have still been the least likely to support both the war in Afghanistan and Iraq. None the less, explains Davis, "enough black people perceived it as a consolidation in nationalism. They finally felt part of the nation. It didn't matter that one million were in prison. It only mattered that they were part of the nation."

Davis is, however, encouraged by the youth of all races. "I'm amazed at the sophistication of a lot of younger people," she says. "We didn't have the ability when I was younger to say all the things we wanted to say. We didn't have the conceptual opportunities for that. A lot of this stuff just rolls off their tongues. Whatever they produce won't be an insurgency of the old type, although I do think that engagement with race and racism will be an important part of it. You have to get over the idea that you win something once and for all and that struggles have to look the same."

The situation they have inherited, however, is "complicated". "I don't envy people trying to give political leadership now," she says. "In the past it was easy. There was black and white."

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2008

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment