This article from the Guardian UK is about with six people who came to our country in the early 80s, attracted by the example and inspiring goals of the Sandinista revolution.

I know three of the six, two of them very well. I don't share the pessimistic outlook ascribed to the six by UK journalist Roy Carroll; and even less do I identify with Jeff Cassel's views as described by Carroll -- a person who expressed elation at the victory of the U.S. sponsored counterrevolutonary coalition (the UNO) in the February 1990 election.

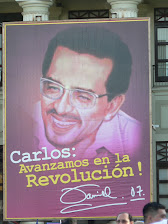

I came to Nicaragua in the mid 80s as a Sandinista (not a Sandalista!, whatever that term is supposed to convey). I remain Sandinista and continue to be a militant of the FSLN. I defend the FSLN government against its pro-imperialist opponents. I defend the decision to join ALBA and ally with Cuba, Venezuela, and indigenous Bolivia. I defend the electoral alliance with the indigenous movement YATAMA on the Caribbean Coast of our country. I defend free health and education, and the progressive social programs of the government.

That said, I also share important criticisms of government policy and actions with sectors of the left in Nicaragua -- moves such as the reactionary decision to support a law criminalizing all abortion, even when that means the death of many women whose lives could be saved by therapeutic procedures.

But, I regret the naivete and cynicism of many who think that the overthrow of the Ortega government (through, for example impeachment by the opposition majority in the National Assembly) would be a good thing, or would make no difference. Such views are often presented as chic or sophisticated by well off middle class folks, and it may be true that a Montealegre government would suit their tastes. But for the poor and oppressed in this country such an outcome would be a disaster. It would also be a blow to the Latin American left in general, and in particular to the Bolivarian revolution in Venezuela and to Cuba.

Make no mistake, if Daniel goes down he will not be replaced by a "non Danielista" Sandinista or by a nice liberal like Edmundo Jarquin (El Feo) of the MRS. He will be replaced by Jaime Morales Carazo, former chief-negotiator for the Contras and longtime PLC leader who only recently allied himself with Daniel Ortega. Or, failing that, someone from either the PLC or the ALN will be named president of the republic. One does not have to be a weatherman to know what that storm would bring with it. Those who want to bring down Ortega are not internationalists, whatever else they may stand for.

Regarding Carroll's article, there is a small error in detail about how Nick Cooke (The translator) got to this country. He did not come as part of an autoworkers delegation. He came down as a member and leader of the first volunteer work brigade sent here by Canadian Action for Nicaragua (CAN), based in Toronto. I recall the details well because I was at that time and for several years the Coordinator of CAN. Nick was endorsed and supported by his union which is how he got the leave from the auto plant to come.

Author Roy Carroll seems to be unaware that Nick is best known in Nicaragua not as a translator but as a writer and former host of a music program on the FM Radio Pirata, a station that was very popular with youth prior to going off the air for lack of resources.

Erick Flakoll, (The bodyguard), is gifted both artistically and linguistically. The author of the article might have mentioned that he is the son of one of Nicaragua and El Salvador’s most gifted poets and writers, Claribel Alegría.

Here is how he is described on the Media 21 website: http://www.m21net.org/spip.php?auteur64

“Erik Flakoll Alegría was born in Chile in 1954 and lived in France, Spain, and England before coming to Nicaragua in 1980. He studied Japanese and Classical Chinese at the School of Oriental and African Studies. Later, he became a journalist in Nicaragua where he has lived for the past 27 years. He was editor of Barricada and is also the founder of Wapponi Productions, a documentary production company. Mr. Flakoll Alegría has made over 30 documentaries dealing with indigenous people, nature, conservation and extreme poverty. He is currently working on a documentary about global warming and how it is affecting the indigenous people who live in the Bosawas biosphere reserve, the second largest forest in the Americas after the Amazon.”

This description accompanied a talk he gave on Global Warming and Climate Change. The text of that can be found at http://media21.squarespace.com/current-articles/2007/8/13/climate-change-and-global-warming-its-up-to-us.html

The article follows immediately below.

The Sandalistas who never left

Thousands of foreigners were so inspired by Nicaragua's communist revolution that they flocked to help the country in the 1980s. When the Sandinistas lost power in 1990, most left, but not all. Now, nearly 30 years later, Rory Carroll tracks down six of them to hear their stories.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2008/feb/12/11

It was the 1980s and Nicaragua's Sandinista revolution was captivating hearts and minds around the world. The olive-uniformed guerrillas had overthrown the hated Somoza dictatorship and were trying to build a more equal society by empowering women, giving peasants land and teaching the illiterate to read. But it was the cold war and where others saw hope, the Reagan administration saw a communist beachhead in central America. It imposed sanctions and sponsored insurgents, the contras, to strangle the revolution.

For the left in Europe, North America and elsewhere Nicaragua became a cause. A popular, progressive and legitimate government in an impoverished country in the developing world was under imperialist attack. It deserved and needed help. Thousands of westerners took planes, boats, buses and motorcycles to this previously unknown backwater between Honduras and Costa Rica. Some were hippies, some were adventurers, some were socialists, many wore Birkenstocks. The Sandalistas were born.

It was a heady time. Central America was a military and ideological battlefield for the US and the Soviet Union. To those who were there it felt like the centre of the world, especially Nicaragua. The revolution was young and fresh and exciting. There was so much to do - schools to be built, coffee to be picked, classes to be taught, the truth to be told. And by God it was fun. If you had dollars, the beer was cheap and you could go dancing every night.

But the war with the contras dragged on, the economy collapsed, the Berlin wall fell and in 1990, during a ceasefire, an election was held. Almost everyone expected the Sandinistas to win. They lost. Nicaraguans were tired of conscription, of shortages, of sacrifice. It was a staggering result. The revolution was over. Washington's glee was boundless. The Sandinistas went into opposition and their foreign guests, the Sandalistas, went home.

Or most of them did. Unnoticed amid the exodus of 1990, some foreigners stayed and have lived quietly in the country ever since. And, in a curious and unexpected epilogue, they have lived to see the Sandinistas' leader, Daniel Ortega, back as president having won the November 2006 election.

Ortega still rails against American imperialism and has nurtured ties with Iran and Venezuela's Hugo Chávez. He has increased spending on anti-poverty programmes, notably health and education, but inflation in Nicaragua is surging, investment is dropping and aid donors, including Britain, are leaving. Ortega's support for a total ban on abortion pleased the Catholic church but alienated traditional Sandinistas, especially women. The IMF and World Bank have been kept sweet. It is an ambiguous and remarkable comeback.

The Guardian visited six of the internacionalistas. Each had a story to tell: why they came, why they stayed and what they think of the Sandinistas' return.

The farmer

Lillian Hall, 47, visited Nicaragua in 1982 as a US college student and instantly fell in love with the revolution. The daughter of middle-class parents radicalised by the civil rights movement and Vietnam, she found her own cause in the countryside where peasants were learning to read and being given land. "There was still hope, still euphoria. People were really pumped up. It was beautiful." She completed her agronomy studies at Cornell to better serve the revolution, and returned in 1984. She lived in rural areas near the Honduran border, where the fighting was heavy, advising peasants on livestock and crops. A greater contribution, she says, was raising awareness on visits back home.

"I'd go to the US, this Ivy Leaguer in the eye of the storm. I had moral authority because I lived in the war zone and could rebut the propaganda and disinformation of the Reagan administration," she says.

When a contra ambush killed her friend Benjamin Linder, a young American volunteer working on an electrification project, Hall identified the body. "The only picture of Ben I have is from the morgue with a bullet in his head. The rest of us were madder than hell and more determined than ever to stay."

Despite the danger, Hall considers that a golden period. "We were younger and thinner, everything was intense, the grief, the happiness, it was intoxicating. There was a real sense of solidarity." She rode horses, bathed in the river and acquired a Nicaraguan husband. "You would walk down the streets of Matagalpa and hear Norwegian, Dutch, Greek, English. We didn't think the revolution would ever end. We thought it would be like Cuba."

The 1990 election was a devastating blow to those hopes. Overnight, a revolution she would have died for ended. "Your whole identity, your passion, your youth, had gone into it," Hall says. She blames the US for destroying a dream that could have blossomed into a model for the world. Nevertheless she stayed, bought a small farm, raised a son and endured what she says was a decade-long collective depression in which neo-liberal economics destroyed Sandinista accomplishments such as land reform.

The 1990s brought individualism, greed and cultural erosion. "Time healing all wounds is the biggest crock of shit," she says. "Ben didn't die, 50,000 people didn't die, so we could have shopping malls and Pizza Hut. Or so that we would have US top 40 pop crap with people listening to Shakira and Britney Spears rather than Nicaraguan music."

In addition to farming, Hall organises tours for US students keen to experience rural life in central America. She thinks it unlikely that the return of the Sandinistas will stop the neo-liberal rot. "It's good that free health and education are being brought back but things have not changed that much."

Despite everything, Hall still adores her adopted country. "They say you can't choose where you'll be born but can choose where you'll die. This is where I want to die," she says.

The translator

Nick Cooke, 53, visited Nicaragua in 1982 as part of a Canadian auto union delegation and was excited by what he saw. "The Sandinistas were trying to do something new. After the US invaded Grenada in 1983 the stakes got higher, so I figured, I'm going to get myself down to Nicaragua before they invade." He returned the hard way: riding his Honda Hawk from Toronto to Managua in 16 days.

He found work translating articles for pro-Sandinista publications. It paid a pittance but he eked out a living. "I was excited," he says. "I think our biggest achievement was raising awareness - a lot more people around the world heard about Nicaragua. I think that contributed to the US decision not to invade."

Cooke married a Nicaraguan and stayed on after 1990. "The 1990 election result was like getting the air kicked out of you, but I figured I'd been here long enough to want to know how the movie turned out." The answer: modest economic and social progress but enduring extremes of inequality and poverty.

Cooke is not optimistic Ortega's return will change that. "Managua is different now, people are more stressed out trying to survive," he says. "In the 80s, you'd ask someone how they were and they'd say 'Eléctrico'. Now they say 'Más o menos', 'so-so'."

His own life has turned out well, though: a successful translation business, property developments on the Pacific coast, a wife and two children he adores. "This is a land of dreams come true. Sometimes I feel like I'm in that Talking Heads song - 'You may find yourself behind the wheel of a large automobile ...'"

The publisher

Louise Calder, now 56, was not looking for revolution; she just wanted to stir up her life a bit. Born in Manchester to a British Rail engineer father, she had graduated from a north London polytechnic, taught for a while and then drifted into social work with teenagers.

On reaching 30 she decided to travel. "I was tired," she explains. "It's exhausting being with angry adolescents and I thought, 'Right, it's time for a break.'" In 1981 she crossed the Atlantic on a Freddie Laker budget flight and worked her way south from Mexico through Belize, Guatemala and Honduras before reaching Nicaragua.

She knew next to nothing about the country but felt welcome. "Quite a few foreigners felt they had a role there and gradually so did I. I was completely infatuated with the ideals. People were putting in all sorts of hours for it, they didn't seem to sleep."

After checking her teaching qualifications, the education ministry posted Calder to Estelí, a northern town, to teach English to somewhat reluctant students. "There was some resistance to the language," she says. "They resented it as imperialist pressure."

She moved to Managua to proof-read a bilingual Sandinista magazine before transferring to Bluefields, a sleepy, humid town on the Caribbean coast, to help run a new monthly magazine called Sunrise. "The idea was to explain the revolution in terms that people could relate to. Some called it Polyannaish. I loved it." Circulation was under 5,000, but in a small community the magazine had a big impact and she stuck with it for almost a decade.

The 1990 election shocked her. The war was the result of US aggression, she says, but in hindsight she considers the movement's defeat inevitable. "People were worn down - the young men coming back in boxes, the rationing. They had sacrificed enough. Not everyone is Che Guevara." The Berlin wall had fallen and the Soviet Union was tottering. "The Sandinista endeavour was not communism, but it was a thing of its time," she says. "The revolution was a wonderful experience for a lot of people, but that's life. Things change."

Since 1993 Calder has had a new career: key-making. A friend who was leaving Bluefields sold her the machine - which until last year was the only one on Nicaragua's entire Atlantic coast - for $500. "It's very easy to do - I could show you in 10 minutes," she says. "And because I've been the only one doing it, I've become famous. At some point everyone needs a key cut."

From a shed in her garden - a riot of hibiscus, coconut, spinach, oregano and banana - she makes 30 keys daily, charging 80p for a house key, but double if it is for a car on the grounds that the owner is likely to be better off. "I couldn't afford to live back in the UK, but that's OK. I'm happy here, it's a very nice town."

The bodyguard

Erik Flakoll, 53, visited Nicaragua in 1980 for a brief stopover, and with only $50 in his pocket, "to see what the fuss was about". He stayed. A black belt in martial arts, and "very enthusiastic" about the revolution, Flakoll found work at a college instructing Sandinista special forces. He became a soldier and survived skirmishes near the Honduran border as the war with the contras escalated. "We were a small unit but feared," he explains. They wore East German uniform cast-offs. "The camouflage was for pine forests, not the tropics, but they were free."

Later, Tomás Borge, the interior minister, hired him as a bodyguard and assistant. "Being a bodyguard is usually very dull. You're hanging around, living other people's lives," says Flakoll. Rising to the rank of sub- commandante, he coordinated security for foreign trips, including one to India, and he also served as an interpreter.

Flakoll's commitment was initially unshakeable. "I was willing to lay my life down for the revolution. The literacy campaigns, the solidarity - all these intangible human values were very important," he says. Only after the war and election defeat did he regret the conscription that rounded up boys as young as 14 to fight. "At the time I was so into it I couldn't see the forest for the trees. Everything was justified by the war."

After 1990, Flakoll joined Barricada, the Sandinista newspaper, and slowly grew disillusioned with party leaders. Ortega's policy of "ruling from below" degenerated into croneyism, he claims. When the party ousted Barricada's editor, Flakoll quit and joined Oxfam as a press officer.

He is now an independent documentary film-maker with three children from three marriages. He lives alone, apparently happily, in his "bachelor pad" on the fringes of Managua. And he still drives the battered Russian-made Lada given to him by the government in the 80s.

The foster mother

For Paulette Goudge, 57, hearing the Clash album Sandinista! changed everything. Inspired by the lyrics, the London social worker joined a solidarity tour to Nicaragua in 1987. She was impressed by the people and dismayed by the conflict. "They were fighting against the United States of America. It didn't seem right."

Goudge learned Spanish, found work at a children's home in Managua and grew close to Guillermina, a two-year-old with learning difficulties thought to be the result of trauma. Goudge adopted her and they moved to Sheffield in 1989. She resumed social work and obtained a PhD while Guillermina attended school, where she was occasionally bullied and called a "Paki".

In 2005, they returned to Nicaragua and with the proceeds from a house-sale built a Spanish-language school and eco-hotel called Mariposa ("Butterfly") in La Concha, south of the capital. It is also a refuge for cats, dogs, horses, birds and even tadpoles. "The builders think I'm mad," laughs Goudge. Guillermina, now 22, is learning Spanish and regularly plays football with local boys, a novelty because she is a girl, has learning difficulties and has a Sheffield accent. "I sound English and I look Nicaraguan," she says, pausing and then amending: "I don't look Nicaraguan when I play football because Nicaraguan girls don't play football."

The fixer

Jeff Cassel, 48, was a working-class backpacker from Sydney working in dead-end jobs in London when, in 1981, he saw a documentary about El Salvador's wars. He bought a pile of Spanish grammar books, dumped his girlfriend, flew to Mexico and travelled down the continent. "When I decide to do something, I really go for it," he say.

Nicaragua blew him away. "I was a left-winger and this was so fresh and exciting," he says. He raised funds in Australia to publish a book of Nicaraguan poetry focusing on female and peasant authors and helped build classrooms, clinics and wells.

Cassel also became a fixer, first for the film Walker, which was directed by Alex Cox, then for journalists who breezed into Managua needing contacts and interepreters. By 1985 doubts gnawed at his commitment.

"Things started not feeling right in paradise." There was the crude anti-American slogans in a literacy campaign. There were the property expropriations and shortages. There was the closure of La Prensa, an outspoken newspaper.

Cassel sheltered some boys who were dodging conscription and took another step away from the revolution when he accompanied his journalist girlfriend to contra lines. "I was led to believe they were US mercenary bandits, but that trip humanised them," he says.

Cassel won bets that the party would lose in 1990. "I was elated." He still considers himself progressive and funds women's medical treatment through a non-government organisation based at his Managua home - a lavish one thanks to property and business investments. "I get little asides from people from the old days because I'm quite comfortable. But I think, fuck you, I've done my bit."

Wednesday, February 13, 2008

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment